An RAN midshipman in HMS Vanguard

by John Jobson

CDRE John Jobson describes his nine months aboard the last of the RN battleships, HMS Vanguard. These recollections are based on his Midshipman’s Journal notes.

It was December 1939: England was at war. Sir Stanley Goodall, the Royal Navy Director of Naval Construction, proposed that the 15-inch gun turrets that had been removed from the two RN battleships, Glorious and Courageous, now aircraft carriers, be utilised for a further battleship in advance of the Lion class that was well downstream.

The rationale for this suggestion was that gun turrets had the longest lead time in battleship construction. Churchill gave his consent, so the project began. The ship was to be named Vanguard, the ninth of that proud name in the history of RN ships. Vanguard was launched in November 1944, completed in April 1946 and sold to the ship breakers in 1960, but she never fired a shot in anger.

HMS Vanguard, dressed overall for Empire Day 1952 at Portland. (RN photo)

Improved King George V

The ship was considerably modified as the experience of WW II fed back into the design office. The bow form gave it a far superior seaworthy performance over the USN Iowa class. Continuous vertical bulkheads improved her surviveability, but this was sometimes at the expense of the crew who had to climb up to the main deck and then down again to get from one watertight compartment to the next. Humidity controls in the boiler and engine rooms were claimed to provide adequate operating conditions in the extremes of the tropics or the arctic.

HMS Vanguard, at 52,000 tons, was capable of 30 knots and she had a complement of 2000. She was the longest, broadest, and heaviest battleship ever to serve in the RN. She was probably the most graceful, but sadly she was fated to be the last. Accepted into service in August, 1946, Vanguard was not tested in war. Instead she played host for the Royal Tour of South Africa between February and May 1947 with the Admiral’s suite refitted for royal use. A further Royal Tour was planned for Vanguard in 1949, this time to Australia.

HMS Vanguard was commissioned 9 August 1946 and displaced 51,440 tons from a 814.5 x 107.6 x 30. 5 feet (249.0m x 32.8 x 9.3 metres) hull. Her armaent included 8 x 15 inch (381mm), 16 x 5.25 inch (133mm), 73 x 40mm Bofors and 4 x 3 pdr guns. Her machinery included eight Admiralty three drum boilers with superheaters and four Parsons single reduction geared turbines that delivered 130,000 shp and drove the ship at 29.75 knots. She was manned by 1500 crew.

Three Australian midshipmen, late of the training cruiser HMS Devonshire, joined Vanguard on the 26th August 1948. Jobson, Stacey and Woolrych had, and still have not, any idea why they were so chosen.

Three RAN MIDNs (left), with three RCN shipmates in Vanguard. The Australians are, from top left, MIDNs Stacey, Woolrych and Jobson. At right is the gunroom.

The size of Vanguard alongside Devonport Dockyard was, to say the least, daunting. She radiated the feeling of power. We joined the night of the ship’s company ball, so the quarterdeck was decorated with flags and coloured lights. We were quickly conveyed to the gunroom; our luggage would follow.

There were three chief levels of living and eating arrangements for officers. The wardroom was used by those of lieutenant rank and above for eating and relaxation. The next was the Commissioned Warrant Officers (CWO) mess. There were many CWOs in those times since promotion from the lower deck to wardroom status was not that common. Finally we had the gunroom, home for the midshipmen and sub lieutenants. The Captain, Fred Parham, by name, had his own quarters.

The gunroom was quite large; it had to be to accommodate its 24 members. The Sub of the gunroom was Neil Anderson, a New Zealander who went on to become the Chief of his Navy. There were three Australians, three Canadians, a NZ pay midshipman and the rest were RN.

Slinging hammocks

Sleeping arrangements were rather primitive. Midshipmen slept in hammocks, which was nothing new, since that had been usual for the past six months in the training cruiser. The space allocated to sling our hammocks in Vanguard was the tiller flat, right aft on the main deck over the mechanisms that moved the rudders. It was very noisy at sea. The trick with sleeping in a hammock is to have it taut; otherwise one wakes up with a very sore back. But a taut hammock is over three feet (one metre) off the ground and, when lying like a sardine next to your neighbour, it is very difficult to get in and out. I gave up and settled for sleeping on the wooden gratings that covered the metal casing over the rudder crosshead.

In those days the RN had boys at sea, lads of about 16. They set up, then lashed and stowed the hammocks in the morning. They were very poorly paid so it was not surprising that there were some thefts. It was our fault. We had locked cupboards allocated, so if we did not take proper care of our possessions, then bad luck.

There were ten big Vanguards in the RN. This is the fifth, “Nelson’s Vanguard“, his Battle of the Nile flagship. A third rate of 1609 tons, she carried 589 crew and 74 guns. After brilliant service between 1787 and 1821 she ended her life as a prison ship and powder hulk.

Ablutions are what makes the navy such a great service, we are told. The poor soldiers in the field rarely have such facilities. Our bathroom, or rather shower room, was some five minutes from our sleeping quarters. To reach it wrapped in a towel and bare feet one had to traverse five watertight doors, opening and closing each in turn. The bathroom was usually awash with water and filled with steam, like a Turkish bath. It made seeing difficult. Service ablution facilities are not the place for the inhibited; one just lets it all hang out. The real problem was to remember to bring back your soap or it would not be there next day.

The meals were generally very good, especially if we had a formal dinner. All three meals were served by stewards, many of whom had friendly banter with most of us, but they never became too familiar. Excellent lads. We generally drank beer because wine was too expensive and we were not allowed spirits. Our “wine bill”, as it was called, was restricted and examined closely every month. Laundry on board was cheap, so the limited money stretched out. Unlike many of our RN contemporaries, the three Australians had no financial support from parents.

Boat handling

Boat handling had been difficult to learn in the training cruiser because there were too many cadets and too few boats. It was therefore a joy to be designated Coxswain of Number One Picket Boat as the first of my series of duties. This twin-screw, 45-foot boat was virtually a miniature destroyer with a Petty Officer on the throttles and three crew. After two hours’ instruction I was cleared to cause as much havoc as I could.

Portland was a work-up venue for RN ships, as well as home to HMS Osprey, an anti-submarine school where I would spend some time as a sub lieutenant. Many officers had homes close by, so it was a rush to man my boat to take them ashore when Vanguard anchored a mile or so off the breakwaters.

Outside the breakwaters there were several large and unlit buoys, unfortunately in direct line with the anchored Vanguard. I had the last boat from shore one night. It must have been about midnight that I collected about 20 well-oiled officers. I knew they wanted to get to bed and the 20-minute trip seemed forever. I made a wrong decision. At full throttle, the Aldis lamp held by the bowman was too weak to give warning of a buoy. I clipped one and lost a propeller. It could have been worse. I could have sunk. My passengers were remarkably calm as I continued on one shaft and discharged them safely aboard. There were no repercussions and after quick repairs I was back in business in a couple of days.

Treacherous sea

Portland can be a treacherous place, in that seas can suddenly roll in. It was some days later that one of our large, tub-like launches, that carried some 60 persons, was smashed to kindling under the boom before it could be hoisted.

It was early September when the sea suddenly got up so much that the picket boat could not be hoisted. Instead, I was ordered to make for harbour and seek shelter. I chose the minesweeper Welfare as my refuge and was well received and fed, as were my crew. Surprise! One of Vanguard‘s Medical Officers who had been escorting a sick sailor ashore chose the same refuge. They had two extra for dinner. Sometime after dinner I received my recall. Off we went, but there were two more trips inshore for me before I could go to bed. We were worked solidly.

Not long after my mishap with the buoy I was having a busy day with visits to Maidstone, Duke of York, Cleopatra and Jutland. Dusk was approaching as I turned for Vanguard, only to find a flotilla of destroyers coming into their night anchorage. It was a hairy time weaving through that lot.

“Clear Lower Deck” for payment was sounded by bugle. All except those on watch assembled on the quarterdeck in long lines. Stepping forward to the paying table the sailor would proffer his cap, announce his name and number and normally receive an envelope with his pay enclosed on the top of his cap. He would take the envelope, replace his cap and salute. Occasionally the paying officer would say “not entitled”, what is called a North Easter. Such a poor man might have been guilty of some offence and fined. Quite offsetting I would imagine.

Bofors firing

But it was time to leave UK shores and seek warmer climes. The multiple Bofors had a shoot. All midshipmen had a turn firing a burst, but the noise was deafening and in those times we had no ear protectors.

Vanguard did not berth at Gibraltar but anchored off. It was ceremonial rehearsal time. The Royal Marine Guard and Band paraded, all officers and sailors dressed in their full whites and Captain’s Rounds started, the first of many. The Rock towered in the distance as the twinkling lights of Gibraltar town slept. Tomorrow was another day.

The 2000 persons on board generated a lot of rubbish. The vegetable matter (and quite probably a lot else) was guided overboard by large and very substantial gash chutes strapped to the ship’s side. Someone must have known the route of the Royal Tour since we were told the ship could not get through the Panama Canal with these attached. So there was an exercise. First take them off, then put them back.

Easing into Malta

There is little room to spare for a battleship in tiny Malta Harbour, as HMS Resolution demonstrates as she eases her way in.

Approaching Malta either by air or sea is an exciting experience. Additionally, there is a mystic thrill that goes with a first time experience. From the foc’s’le I could see Malta so well, its bright yellow sandstone erupting from the blue of the sea. The Grand Harbour is a difficult entry for a battleship, but the weather was kind and we crept in to our buoy in Bighi Bay, just inside the breakwater.

RN Base, Malta

Malta was still an RN base. Evidence of damage from WW II was not great when viewed from our location. There were flotillas of destroyers up Sliema Creek, a carrier in dock and several cruisers in view.

A Maltese dghaisa, with the rower characteristically facing forward.

The hundreds of dghaisas gave the place a busy look. Sadly the dghaisa, the transport used to get ashore for a generation of RN officers, has died. There was not a sign of one when I visited in 1994.

For promotion, being a Gunnery Officer seemed a good choice. It was the “in thing”, especially in a battleship where the guns were the gods. It was therefore a great thrill, as part of my general naval education, to be taken to the bowels of the ship to the Transmitting Station (TS). It was really down deep. Forget escape if the ship was torpedoed.

Here in a sort of nightclub gloom, figures (often Marines) huddled over their dimly lit tables. They seemed as though they wanted to hit the jackpot as they turned the handles. This was all too much for me, but in simple terms they were transmitting information to the guns: where to train, elevate and what fuse to use. The system required others in the turret to match pointers to apply the information sent by the TS.

Main armament

I was fortunate to be on the bridge during some 15-inch firings. One could actually see the shell leave the barrel.

While on the matters of the bridge, the Midshipman of the Watch (MOW) had three duties. The first was to observe, the second to run errands, and the third to make Ki at night. This beverage was a cruel imitation of highly sweetened thick cocoa. I must emphasise that after several months one felt quite capable of assuming the duties of Officer of the Watch.

USS Iowa, BB61, a sturdy and durable WW II Vanguard contemporary, fired many an angry shot and saw extensive service until she paid off finally 26 October 1990. Here, she fires her 16-inch main armament. (USN photo by PMA J.F. Elliot.)

In order to understand the enormity of large calibre weapons one has to experience the daily ritual of magazine rounds, a rather pathetic practice in view of the non-event of a disaster from lack of such. But such was the case that every day one had to go to the depths of the ship to check magazines and shell rooms for inflammable matter.

My turn came on a Saturday. The hatch leading to the magazine was steel, one foot thick with a chain hoist to raise and lower it. It was near lunchtime and I was really at the bottom of the ship, eerie but fascinating to be among all this cold metal. There was a clang, and I knew what that meant, I was trapped. There was a telephone but it had no call-up system, it had to be manned at each end. My luck held. I could hear voices in the turret to which the telephone was connected; bless them for working overtime. I attracted attention by a shell type order lever that indicated to the shell room crew what type of shell was wanted. Each time it was moved, it gave a clang. I gave this device a hell of a workout.

Thankfully, Ordnance Artificers are an intelligent bunch and they let me out. I would not have died but I would have been very hungry and cold by next day. Lesson: if you go down a hole, leave your cap at the top to indicate that someone is below. Notice how lessons are being learned for the future?

The WW I Dreadnought battleship HMS Vanguard was destroyed by a mysterious magazine explosion at Scapa Flow 9 July 1917. Only two of her 700 crew aboard survived.

Vanguard‘s quarterdeck was an immense space, the wooden deck gleamed. It just seemed to go on forever. The Officer of the Watch (OOW) and his Midshipman (MOW) were in charge of this magical place. It was the site for receiving top officials, sometimes together with Guard and Band. It was also the site for receptions, assemblies of ship’s company, cinema shows, even for boxing matches; yes it was Vanguard‘s reception room.

This immense space sometimes had a roof, called an awning. Can you imagine the size and weight of this huge piece of canvas? Well, it had to be handled and with techniques and sufficient men it was manageable. Once set, it was the responsibility of the MOW to manage it. “Sloping” is a process used when the wind strengthens. Every second downhaul is taken to the deck, to restrict the wind from getting underneath the awning and blowing it off. I never lost a quarterdeck awning.

The MOW, dressed in full whites with a telescope as his badge of office, virtually ran the ship’s routine in harbour, supervised by the OOW. Routines were listed, but one tricky part was watching to salute passing Flag Officers and foreign ships, return salutes from junior ships and return the dipping of the ensign to merchant ships. Boat routines were sometimes difficult to plan when a special call was made for a boat for a senior officer.

Marsa Social Club

There was little purpose in going ashore in Malta. There was nothing to buy, no shows and the beer tasted salty. One never suffered from constipation in Malta. Small horse-drawn carriages, called Gharries, complete with tinkling bells, were the principal source of transport. Only the tennis courts of the Marsa Social Club provided any entertainment that could not be had onboard.

The workup continued while the Royal Marines Band entertained by playing numbers from the latest London shows. The Captain reviewed the ceremonial of manning ship where the whole of the crew in best dress lined the edges of all above-water decks.

Leaving the buoy in Bighi Bay was quite a manoeuvre. From the foc’s’le I had a grandstand view of the 13th October departure. To start with, the buoy with a blacksmith astride was hauled out of the water before the cable was broken. Then the attendant motor cutter snagged a rope around its propeller and finally the tug snapped its towing wire. The captain was relieved when we finally cleared the breakwater and Vanguard was at sea.

More gunnery trials followed, this time with the anti-aircraft armament. What an impressive cavalcade of noise, but as the aircraft and towed target calmly flew past, the Gunnery Officer’s remarked, “Please, a few tattered wings at least on the next run.”

The only time midshipmen were allowed spirits was when they were entertained or when they were entertaining the gunroom members of another ship. The favourite tipple was gin and orange. This often had disastrous consequences. Once, when Vanguard was in Malta, a splendidly attired midshipman rushed into the gunroom en route to a party ashore after one such entertainment had just finished. One over-imbiber rose from his horizontal position and decided the gin and orange was no longer welcome in his stomach. The splendidly attired MIDN collected the lot. Yes, he was late for the party.

The workup off Malta completed, Vanguard turned for her Devonport home for Christmas. Truman was re-elected and Prince Charles was born. “Splice the Mainbrace”.

Back to blue winter uniforms and the chill that only Devonport can provide. Storing continued, including all those special stocks of souvenirs for sale during the Royal Tour. This included hundreds of dozens of specially brewed beer, complete with distinctive labels and the special wines we embarked at Gibraltar.

At dawn on the 23rd of November, “Clear Lower Deck” was sounded. With all the ship’s company assembled, the Captain made the following announcement: “The King is ill. The Royal Tour has been postponed.” We know now that this was a cancellation, not a postponement.

Christmas leave

It was time for Christmas leave. I had been away from Australia for over a year. After a really good Christmas with my foster-parents, who lived near Chichester, I returned to Vanguard on the 2nd January 1949. Vanguard had been designated as the flagship of Admiral Power, Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean. A golden year was about to begin for the good ship Vanguard. The Admiral arrived and reoccupied his quarters vacated for the royals.

The MIDNs were shown over various shore establishments and supply depots, they engaged in damage control and first aid courses and started their acquaint times of the engineering, gunnery and communications departments. Watch duties continued, so did the nightly signal exercises.

On the 3rd February 1949, HMS Vanguard sailed for the Mediterranean. At sea, a midshipman’s main duty was as Assistant Divisional Officer, inspecting mess decks, etc. The journal had to be written up, acquaint courses with other ship departments continued and, of course, duty as MOW.

Gibraltar

Gibraltar Harbour groaned with the ships of many navies. The narrow streets were alive with service personnel, much to the delight of the predominantly Indian shopkeepers. The “girlie shows” were packed with often a thousand randy sailors. Only officers were allowed to go ashore in plain clothes and only officers were allowed across the border into Spain.

The town of La Linea was a walk across the airstrip and the border-controlled area. It was a Saturday when three members of the gunroom ventured across. We consumed a bottle of excellent Tio Pepe sherry and a plate of roasted almonds before purchasing our threepenny bottle into which was put our threepenny purchase of red wine. Armed with our threepenny cushion we paid our one shilling entrance to the bull ring. A most uninspiring display of butchery followed. It must have been beginner’s day. Cushions were hurled into the ring and boos rang out. I have never been or wished to see another bullfight. That week the Snotty’s Nurse (the supervisor of my journal diary) noted, “You must comment more on the detail of onboard life as you do about your shore side activities.” However I knew what made for the best reading. I was totally absorbed observing the different modes of life of different cultures.

Young men about town

MIDNs Jobson (left) and Woolrych step ashore to terrorise (or be terrorised by) the local Spanish fleshpots.

Another day ashore, Woolrych and I ventured a walk further into Spain to the village of San Roque. It looked dusty and poor with soldiers playing soccer in their overcoats. We wondered if perhaps they had little on underneath. It was quite hot. At least the eucalyptus trees reminded us of home.

Editor Vanguard Daily News

A new duty was thrust my way: Editor of the Vanguard Daily News. In the absence of newspapers it was read at breakfast by most officers and many of the crew. My office was ten levels up in the superstructure. There, at night, I collected a six-foot length of intercepts that the communicators had copied from the various news agencies. My task was to select suitable topics, condense them as required, add local ship news and, hopefully, a cartoon.

I had to type my selected news to fill at least two sides of a foolscap sheet. With two-finger typing this task was rarely finished by midnight before returning the master copies to the communicators for reproduction and distribution. This was quite an enjoyable task and good training.

Vanguard sailed for Algiers on one of many goodwill visits. She dropped her two bower anchors and then backed her stern to a finger wharf where wire hawsers held her in position. She looked like a praying mantis with legs stretched out.

Ashore, there was a cocktail party where short French stewards tottered around with huge magnums of champagne. The US guests stuck to their scotch on the rocks. A bunch of midshipmen, thinking there was safety in numbers, ventured into the famed Kasbah to view the girls. All escaped unhurt, with the only casualty a stolen watch.

I should not have accepted an invitation to the local University Ball. With no host, no partners and having to buy our own drinks, it was a long dry night.

About 0300 some kind soul drove me back to the ship. The wind had sprung up and the pontoons connecting the ship to shore had been removed. Once onboard I was told that I had the 0400 to 0800 anchor watch. This was quite a responsibility. I was on the bridge by myself taking fixes every ten minutes to check if the ship had dragged her anchor. It was a long night. Fortunately, lack of money had left me sober from the Ball.

Algiers to Toulon was but a short haul. Apart from the almost constant parading of Guard and Band for one VIP after another, it was forgettable. Naples, the next port of call was another matter. The use of the local bus to reach a beach for a swim put me off garlic for some 20 years. But I was one of the lucky ones to go to Capri and the Blue Grotto, using the ship’s picket boat.

Another day we had a bus excursion to Sorrento by the cliff road. This was quite hair-raising when the coach lost a tyre. Fortunately it was an inside tyre, so the bus veered into rather than over the cliff.

Barter system

Souvenirs were bought on the barter system; I used cigarettes for my meagre purchases. But it was too long a day. I fell asleep at the opera that night.

The dress for midshipmen in charge of boats was long white jacket and blue trousers, smart and sensible, since to gain access to your boat meant climbing over a boom (an enormous wooden pole that projects horizontally from the ship’s side) and then descending by a rope ladder. We had a deal of experience at that exercise at Naval College, but with a sea running it is not quite so easy.

Returning to our familiar berth in Malta, the admiral and his staff moved ashore and we started some weeks of recreation and sport. I had made my way into the ship’s first eleven. Mind you it was not a crash hot team. The Royal Marine Major, who loved his cricket, told me that unless he had had a bag with bat and pads he would never have made the team. He was right. He was always marginal.

The Vanguard First Eleven. MIDN Stacey is second from right, top row. MIDN Jobson is second from right, front row.

Stacey and I became permanent members. Strangely, we always relied on sailors for fast bowling. One lad in particular had the fire in his belly to frighten the opposition. A difficult task with a mainly officer team, but he was a good big lad and fitted in well. I slotted into the opening combination of MIDN Jobson and Engineer LEUT Steve Sharrock. Over the next six months we steered our team to more wins than losses. It is amazing how sport success brings one to the notice of the higher ranks. Of 18 games played, we won 10, drew 2 and lost 6; not too bad.

While most of this text seems to be related to port visits, a midshipman was never allowed to be idle. Take navigation time for example. I recorded that it took until 0100 to complete my navigational task book, with three hours’ sleep before my next watch. As it should be. The onboard cinema was a proper cinema and was a great source of entertainment. The RN had an arrangement with the UK film distributors such that quite recent films were available. There were separate sessions for ship’s company, chief and petty officers and officers.

Red infuriator

The wardroom wine caterer made a bad mistake. He purchased copious bottles of Algerian red. To the qualified opinion of the wardroom it was “cat’s piss”. The gunroom taste was less subtle so we inherited a cache of wine at a shilling (ten cents) a bottle. Despite the taste, the alcoholic content was there. Put together, Sunday cinema and Algerian red, you had a hoot of a time.

My Action Station was Gun Direction Officer Visual (Port). For this task I was given charge of a huge set of binoculars mounted on a trainable stand. The idea was that young eyes would spot an approaching enemy aircraft, get it in the cross wires of the binoculars and then press a bell to alert the radar where to look and lock on. The trouble was that the aircraft were fast and our process slow; but I did enjoy the fresh air.

Out we went again, this time for a short trip to Tripoli. For reasons unknown to me, we had another game of cricket.

We had another week in Malta and then it was off to Venice, where Vanguard anchored many miles off shore. A cocktail party bringing oh so well-dressed members of the Venetian community very nearly ended in multiple divorces. I was in charge of the picket boat bringing the guests aboard. The boat heaved some ten feet in the swell alongside the accommodation ladder. It was a situation when, one at a time, a guest leaped, or more particularly was lifted, from the boat to the lower platform. I must admit it was scary but I did not mind the screams because my job was to keep the boat in position. We did not lose or damage a guest but it is my guess that some of those visitors will remember that occasion for the rest of their lives.

Princess Margaret inspects the ship’s company at Venice.

While at Venice, Princess Margaret visited and inspected the ship with the ship’s company at Divisions. One thinks that this was part of the Royals effort to say sorry to the ship’s company for the cancellation of the Royal Tour. Whatever, I obtained an invitation to her official lunch. In fact I sat nearly opposite her. But at 19 years of age I was devoid of conversation and, I suppose wisely, kept my mouth closed during a really superb lunch.

My engineering acquaintance time had started. Rounds were totally exhausting, as one climbed down three levels by ladder, up again and then down. Luckily, my cricket opener partner was my allocated engineering minder, so we inspected the whole ship, exploring bilges and all miscellaneous compartments that contained mechanical equipment. It was interesting. Who would have thought that many years later I would be an engineer? The entrance to the boiler rooms was through double doors, since the boilers had to maintain a positive pressure. Whatever the words were in the specification for comfort, I can assure you that the temperature and humidity of all the spaces were uncomfortable. Coming out of the boiler rooms one was a lather of sweat.

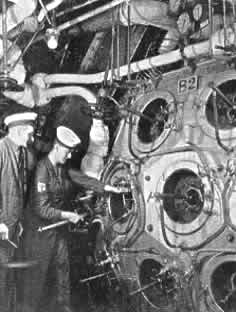

Preparing to flash up Vanguard‘s B2 boiler.

A jubilant midshipman, not to be named, raced into the gunroom with water pistol one day and gave me a full serve. Not impressed, I rewarded him with a bunch of fives. It was on, the Colonials against the Brits. Without too much blood, we let off steam and thereafter the new and the old became a team of one in the gunroom.

The admiral and staff rejoined for exercises with the Mediterranean Fleet.

A Blue Force was based on Spain and Portugal. Red Force held the North African coast. Scenarios were put together. Red Force, returning from raids in the Atlantic, was to be prevented from entering the Mediterranean by Blue. Submarine lines were set, spies were lodged on the Rock and destroyers were disguised as cruisers to confuse the pilots. What a grand show. MIDNs were not told a lot. There were two battleships, three carriers, five submarines, seven cruisers and sixteen destroyers; proof that the RN was still a maritime power. But in the end airpower won the day. There was a big wash-up at Gibraltar.

The Med. fleet dispersed but Vanguard headed east to Port Said. What a Gilbert and Sullivan comedy was played out here, as every sort of dignitary paid a call, the Guard and Band were exhausted; the bugler all blown out. During the cruise there were 35 Guards and Band and three Royal Guards of 100 strong. Vanguard berthed on the Port Fouad side of the canal, so the MOW had a busy time with boats and visitors, plus a grandstand view of all the Suez traffic. This had its problems because it was a custom that all merchant vessels dipped their ensign when passing an RN Warship. This had to be recognised by the dipping of our own ensign. Even the gracious white liner RMS Strathaird dipped as she passed by.

Two days of cricket

Two days of cricket against the Army and a grand invitation to dinner and show by a General and his wife was my social bit. Thereafter I was duty. But what fun it was when the local magician, called a Gully-Gully man, performed on the quarterdeck with his traditional tricks and finale of producing a dozen or so chirping yellow chickens from everywhere. I must say that I liked the Egyptians.

The next port of call was Beirut, still in its heyday. English staff of the Iraq Petroleum Company, most without wives, were keen for a cricket game. The Vanguard XI was coached to a place called Tripoli. En route we noted that a number of the bridges had a rising sun emblem on them. They had been constructed by Australian Army Engineers. The cricket was followed by a really top class buffet dinner. The oil companies knew how to look after their staff.

Next day the ship weighed anchor in a hurry and worked up to full speed after a quartermaster reported seeing a diver in the water. We did not have an explosion so we either loosened any limpet mine or it was a false alarm. But even in those early days a threat existed; the area was dangerous.

The Eastern Med.

Vanguard in the placid Mediterranean.

Away we went again, this time to Athens via Rhodes and Salonika. By good fortune it was time for my pilotage training so I had a top view of the hundreds of islands cluttering the ocean. When the sea is calm, the Mediterranean is a glorious place in which to travel.

Salonika. Here the gunroom socialised with a young group of English Army officers from the Ocks and Bucks. They were quite mad. At the local Macedonia Club they insisted at practising parachute jumps off the balcony using the table umbrellas. Luckily there were no breakages. We played more cricket against the local expats.

Then it was on to Athens and one particular magical evening organised by a General Downes. Everyone, including the eight invited MIDNs, had a partner. The dinner, served on a balcony on a balmy night, was followed by dancing. Those long years at Naval College were rewarded by one memorable night. Remember it was still an era of “Dance but don’t touch”. Next day for some reason I was presented to King Paul. But that was it. Duty called for the rest of our stay in Greece.

Taranto was the next on the list of ports to visit. Considering what the RN did to the Italian Fleet not so many years before, one was surprised at the charming Italian officers. My first XI opener and I decided to forgo the local dance that had been arranged and play night tennis at the officers club. Whatever the faults of Mussolini, he was a great provider for his officer corps. The club was a palace of marble and it came with impeccable service. Unfortunately, the tennis court lights interfered with the outside cinema show. We were requested to stop. We did and retired to the bar.

Fleet regatta

Vanguard met the Fleet at Navarino on the west coast of Greece for the Fleet Regatta and for the C-in-C’s finale. Back to Malta and a short trip to Tripoli to collect Amir Sennusi of Cyrenaica for passage to Marseilles; the Foreign Office must have had some reason.

Before Vanguard went home it had one more duty to perform: to drink out the thousands of cans of beer, especially brewed and labelled for the Royal Tour. Enormous baskets on Vanguard‘s quarterdeck gave evidence supporting that aim, all full to the brim with empties.

Gibraltar. Duty free shopping day. This was the end of a remarkable tour of the Mediterranean.

The time in the Mediterranean was without doubt more than adequate compensation for the loss of the Royal Cruise. The ship steamed 14,350 miles, burnt 13,213 tons of oil, made 33,130 tons of water, baked 20,000 doughnuts, used 4903 tins of brass polish, sold 124,572 ice creams, fired 727 rounds from the saluting guns and 75,844 rounds from the real guns; replaced 12,430 light globes and finally the ship’s company were paid 73,605 pounds six shillings and one penny.

Monday 25th July 1949. Place Devonport. The Ball. I provided a future Admiral RN with his date. Mine was her friend, but I forgot her surname when it was time to introduce her to the Captain who was receiving guests.

It was a great evening, a fitting farewell to some nine months serving in Vanguard. I was still only 19 years of age but after a very lacklustre start I was growing more mature with every year. The aircraft carrier HMS Vengeance, a new challenge, lay ahead. Vanguard IX just faded into history as the last of an illustrious line of Royal Navy battleships.

HMS Vanguard X is a nuclear submarine of 15,900 tons. Her 135 crew operate 16 Trident II and two D2 missiles, plus four 21-inch torpedo tubes.

Enjoyed reading his account of the Med Cruise. I was also on it as a 19 year old AB and it really annoyed me that the Middies were allowed to cox’n the launches as they would never again have to do that chore after promotion to higher rank whilst us seaman who were also crew on the launches were never given the chance to handle them though we would have to pass a boat handlinng test for promotion to Leading Seaman and above. This happened to me later on whilst serving on the Austalian Carrier HMAS Sydney. I failed the the boat handling test whilst trying to pass for Leading Seaman simply because I had never ever received any instructions or had practical experience handling one,