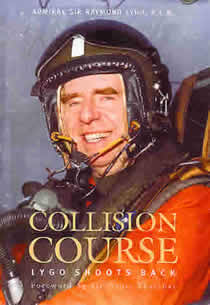

ADML Ray Lygo

Book review by Fred Lane

Lygo R. Collision course: Lygo shoots back. The Book Guild: Lewes 2002. 551pp plus glossary, index and photographs.

Internet cost: $50 incl postage.

Ray Lygo, worked as a printer’s copyholder before joining the RN as a Naval Airman Second Class in 1942 . He never sat for a School Certificate but coerced his way past the Recruiting CPO’s desk by insisting that his Air Training Corps Cadet service was sufficient for aircrew. A distinguished career followed, as a Fleet Air Arm fighter pilot, Qualified Flying Instructor (QFI) and Commanding Officer of a number of ships and squadrons. He retired at age 51 as ADML Sir Raymond Lygo, KCB, First Sea Lord, joining British Aerospace and becoming chairman of a number of illustrious British companies.

Choppy start

He starts his book with an unfortunate fancy-schmancy literary device used by writers of lesser ability of suddenly chopping back and forth from his collision as Captain of Ark Royal with a Russian destroyer in the Mediterranean to negotiating important contracts as Chairman of British Aerospace a couple of decades later. He also makes minor errors, like reversing the RN/USN Landing Signals Officer (Batsman) signals. Bear with him. The rest of the book is worth these painful Lorenz-style imprinting events.

Dozens of names familiar to Australians pop out of the pages. Ex-FOCAF Chas Eccles is mentioned and Mike Fell, 20th CAG Commander and Sydney CAG Commander in Korea, appears from time to time. Corky Corkhill is another. Barney Barron, later CO of RAN 805 Squadron in 1959-60, is correctly identified as one of those highly competent “terrible twins of Culdrose” in 1953.

Lygo’s autobiography spans an important period in the RN’s history. He describes how the RN finally shook itself clear of the 1930s Fleet Air Arm malaise, at considerable cost, then slumped from a potent carrier-backed force into a mere rump of its former self. He shows how the RN lost three of its four big aircraft carriers early in WW II due, in no small measure, to mismanagement. As a Seafire pilot in the Pacific during WW II, he learned the hard lessons about operating a land-based machine converted for carrier use, compared with American purpose-built carrier aircraft like the F4U Corsair.

He graphically describes the almost constant RAF aircraft versus RN carrier battles inside Whitehall that ranged from sniping to downright lies. Tragically, when the dust settled and the RAF won their case, the RN lost their proposed new aircraft carrier and the major capabilities that went with it, but the RAF did not get their TSR2 and other expected aircraft. Neither did the non-aviation admirals, who frequently supported the RAF position, get their anticipated cruisers and destroyers. The money simply disappeared into general revenue. “Aircraft carrier” became such a pejorative term that awkward semantics like “through deck cruiser” had to be invented.

Importantly, as Lygo says, the eminently obvious but overlooked solution was “a larger class of aircraft carriers, built to commercial standards and therefore much cheaper, concentrating all their build into the flying facilities, leaving it to the escort vessels to provide protection apart from point defence,” (p315).

In Lygo’s post-WW II era, frigates and destroyers not only performed their war-related duties but also important diplomatic missions. Lygo describes how he participated in at least three of these in command of ships as a LCDR and CMDR, during visits to Grenada in the Caribbean, Waterford in Ireland and Algeciras in Spain, all without a “Minister-for-Everything” peering over his shoulder.

Australia, move over

In one of the never-ending internecine Fleet Air Arm versus RAF carrier battles, the RAF claimed that they could comfortably conduct both surveillance and fighter duties over the oceans from existing (or planned) bases. Therefore aircraft carriers were unnecessary. The money would be better spent on RAF aircraft. This lie was exposed during Lygo’s watch as Deputy Director of Naval Air Warfare when he found the RAF using deliberately doctored maps. They had moved Australia some 200 miles west to bolster their Indian Ocean argument.

Later, in command of Ark Royal, he was challenged with attacking an RAF base while on passage from Gibraltar to the UK. The RAF had ample surveillance and fighter forces to defend against this attack as well as a good idea about its timing. Lygo simply detached his support group of replenishment ships and some escorts to look like a carrier force attacking from the west. He even sent aircraft out to simulate touch and goes on a big tanker. Meanwhile, keeping radar and radio silence, he closed from the south and launched an unopposed “nuclear” strike with a Scimitar, in effect wiping out the RAF base.

Biased decisions

One questionable decision during his Ministry of Defence watch was an expensive industry-related policy to design and develop new afterburning Rolls Royce Spey engines to replace the tried, true and sufficient Pratt and Whitney J79s in the American Phantoms purchased for the RN and RAF. On the one hand, money was squandered for no real military purpose, while vital naval concerns, such as a replacement carrier, were obfuscated. Another time, a big team visited the USA to investigate an offer of three ex-USN carriers at bargain prices. Not one naval aviator was on the team. Not surprisingly, the team declined the offer. Crucial operations-related decisions were sometimes delegated to totally unqualified but politically-connected “scientists”, contaminated by doctored or incomplete data.

He was also lucky. He was a passenger in a 12-seater naval DeHavilland Heron when the pilot flew it into trees during an instrument letdown to RAF Base Turnhouse, Scotland (p331). There was a “great deal of structural damage”, the wings were “almost in ribbons” and a small electrical fire started in the fuselage. However, a hole magically appeared in the clouds, with a runway straight ahead, so the pilot threw it on, flapless at 120 knots, without inflicting further damage.

Flash up checklists

Best of all, Lygo describes the era when flying was fun and the navy was not so much a bean-counter’s profession as an adventure. Lygo was responsible for brilliant practical jokes and other stunts, which kept everyone on their toes and built morale. At the same time it was Lygo who introduced a now-standard check list, like a pilot’s check list, for flashing up boilers. As an A1 QFI, Lygo adapted flying instructional techniques to the seamanship profession. As a pilot, he was always aware of the bottom line: know your limits, in the air and on the ground.

In civilian life he applied the lessons he learned as a divisional officer and commanding officer. Whether dealing with unions or negotiating major company takeovers Lygo always wanted to know what was the predominant aim and whether the data were true. He found no substitute for “clear lower deck “eyeball-to-eyeball talks” and shop-floor “rounds”.