This article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on 10 March 2022. It is a reminder of the selfless service that so many have given to the RAN and their country.

Navy’s top clearance diver led demolition of WWII bombs and mines

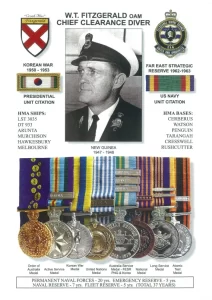

WILLIAM TERENCE FITZGERALD: March 23, 1929-March 5, 2022

William (Bill) Fitzgerald was a legendary clearance diver with the Royal Australian Navy who was charged with demolition of ordnance in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War.

Wearing the heavy and cumbersome equipment of the time, he would dive on the American bombs and Japanese and British mines left behind in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Often, low water visibility meant that he worked at great personal risk, hardly able to see his hand in front of his metal helmet.

In later operations he dived on an Australian atomic test site, despite being told by the bomb’s developer that the work would leave him sterile for five years. He also made a high-risk dive to the depth of 79 metres to free the sluice gates of the Eucumbene Dam in the Snowy Mountains.

William Terence Fitzgerald was born at the Cottage Hospital in Chatswood on March 23, 1929, one of three sons and three sisters born to father Sydney William Fitzgerald, who also had a prominent Royal Australian Navy career, and mother Florence (nee Bavistock) who was born in Southsea near Portsmouth. They met when Sydney was stationed overseas, and they would meet under the clock at Southsea railway station.

Sydney Fitzgerald, who was enlisted as chief petty officer’s torpedoman mate, was a survivor of the attack on the destroyer HMAS Nestor in June 1942 when the ship, part of a convoy taking supplies to Malta, came under air attack from German dive bombers and had to be scuttled the next day. In 1944 he was admitted into care suffering from what was then known as shell shock.

Bill entered the RAN on May 30, 1946 keen to follow in his father’s footsteps, and when told he was to be a gunner, stood his ground saying: “I’m not going to be a gunner, I’m going to be a torpedo man.” He won the day.

Initially he trained as a pump hand for a standard diver, before volunteering for the three-week-long RMS (Render Mines Safe) course held at HMAS Penguin on Middle Head. In September 1947 he posted to HMAS Tarangau, headquarters of the Papua-New Guinea Division of the Royal Australian Navy.

Interviewed about his service at the age of 90, he said: “I was pulling bombs out from under wharves and God knows what else. World War Two was supposed to be finished, and it wasn’t.

“[On one occasion] I donned a modified diving set, went down and pulled the bombs out [and] they were 500-pound armour-piercing Japanese bombs. Jap navy bombs have got rivets on them, Jap army bombs are three-inch skinned. They are all tail-fused. Took the fuses out, pulled the bombs up, took them away and blew them up.”

He spent 12 months in New Guinea extending his knowledge from WWII bomb disposal experts while working on the demolition of ordnance left behind in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

In September 1948 he returned from New Guinea to Australia and met his wife, Madge, at a dance at Luna Park. He had gone to her aid after the 16-year-old fainted, having inhaled from her first cigarette.

During the Korean War in 1952 he served on the Bay-class frigate HMAS Murchison, and was trapped in the Han River when the ship “with a few holes in it” came under continuous machine gun fire, 180 metres from the shore. “I did all the sounding in that river to get the ship into a position to bombard – 8000 soundings we did, by lead and line,” he said.

Fitzgerald joined HMAS Hawkesbury in 1952, where he was involved in the recovery of items from the Monte Bello Islands atomic test site in Western Australia. The British test involved detonation of a 25 kiloton nuclear fission bomb to gauge impact on foodstuffs, shipping and defensive structures.

He recalled he was informed on deck by the bomb’s developer, Sir William Penney, about the inherent risks of the job: “He said that with the work you have to do here, you will be sterile for five years. We still did the job. We were ordered to do it, and we did it.

“I had two sons before the Monte Bello and didn’t have a daughter until five years after, who was born on Anzac Day.” He had two sons and then two daughters.

In 1955, there was a requirement for the first clearance divers to be called up into the navy. Fitzgerald was considered worthy to be accepted, even though he was considered overage at 25. He successfully passed and became one of the first clearance divers for the RAN at the rank of petty officer.

He said the requirement for a good clearance diver was “to be above average intelligence, young, healthy [and] have a can-do attitude. The impossible sometimes takes a bit longer and so long as you remember that, and you keep your mouth shut, you will make a good clearance diver.”

Following the course, he went on to become a diving instructor at Rushcutters Bay. His exploits included diving on the wreck of the destroyer USS Peary in Darwin, sunk at anchor in 1942 by Japanese aircraft, to remove weaponry before she was cut up. The dives on Peary could only last one hour a day at slack water at low or high tide because of 25 knot currents. In almost nil visibility, the dive involved rendering safe the numerous torpedo warheads.

The Eastern Area Mobile Clearance Diving Team was formed in 1956-1957. Fitzgerald became its chief before eventually it became Clearance Diving Team One, which it remains today. In the late 1950s the team had only 12 people, but today it is 60 members strong.

In 1962, Fitzgerald was one of the team involved in a project at the Eucumbene Dam to free the sluice gates at a depth of around 79 metres – a job that took nearly six months to complete. After 12 minutes breathing air on the initial dive he was suffering “pretty bad” narcosis, a reversible change in consciousness as gases at high pressure cause an anaesthetic effect. He surfaced feeling terrible, believing he was going to get the staggers (decompression sickness), but after being laid down and given pure oxygen he was considered by the underwater medical specialist to be OK.

In 1963 he dived on the British submarine HMS Tabard, which was involved in a navy exercise with HMAS Melbourne. The submarine had developed technical problems and was unable to dive. He found that a main inlet valve was blocked by sand and effected the repair, underwater and alone, with the aid of a seven-pound hammer.

On a lighter note, Fitzgerald tells of playing rugby for the navy diving team up against their main rivals, a team from the HMAS Watson training school at South Head. The divers used to train in overalls in the water and in bare feet.

In a clash at Rushcutters Bay Park, the Watson team was leading 15-0 at half-time. He said: “We went behind the dressing shed, had a whiff of oxygen and half a glass of rum, took our boots off and beat them 30-15.”

He also coached the water polo team, which trained in overalls with three-pound lead weights in the pockets so that when they actually played a game, “they were walking on water”.

Fitzgerald finished his full-time service as a chief instructor for all courses at HMAS Rushcutter and transitioned from the permanent service in 1966. But he continued to serve as a reservist until 1984 – totalling 37 years, 138 days of total service.

His love of and interest in diving carried over into civilian life. He became a private diving instructor and helped to develop and establish the hyperbaric unit at Prince Henry Hospital in Sydney, delivering over 1500 therapies over four years. He was then asked to join the CSIRO to train and supervise their marine biologists in diving for a further five years.

In 1976, he took over a position with a prominent safety equipment firm and became their sales manager, discussing the safety equipment and breathing apparatus issues with managers in a wide variety of private and public industries, including the RAN, and supplying equipment to meet their needs.

In the Queen’s Birthday Honours List of 1999, Fitzgerald received an OAM for “service to diving, and to the development and training in the use of life support breathing apparatus” – a unique citation for a unique person with a unique skill set.

Speaking at the nursing home in Warriewood, he said: “If I had my time over again, I would do it exactly the same.”

Bill Fitzgerald is survived by Madge, Debra, Rebecca, Terry and Steven, sibling Gloria and six grandchildren, one of whom predeceased his grandfather.