USN Carrier Evolution IV: Purpose-built ships

Fourth article in a series by Scot MacDonald. Reprinted with permission: Naval Aviation News, June 1962, pp 22- 27.

“Such remarks as I may have to make as to the nature and extent of the air force required by the Navy will be based upon the assumption that the airplane is now a major force, and is becoming daily more efficient and its weapons more deadly … that therefore even a small, high-speed carrier alone can destroy or disable a battleship alone, that a fleet whose carriers give it command of the air over the enemy fleet can defeat the latter, that the fast carrier is the capital ship of the future. Based upon these assumptions, it is evident that our policy in regard to the Navy air force should be command of the air over the fleet of any possible enemy.” ADML William S. Sims, USN, October 14, 1925.

Plenipotentiaries of the United States, the British Empire, France, Italy and Japan met in Washington in the early Twenties to reach an agreement on the limitation of naval armament. The treaty they signed on 6 February 1922 had a profound effect on the evolution of aircraft carriers.

From the time the U.S. Navy first embarked upon a carrier-building program, it was faced with tonnage limitations established by this treaty.

131,000 tons

The total tonnage for aircraft carriers of each of the contracting powers permitted the U.S. and Great Britain 131,000 tons each, France and Italy 60,000 tons each, and Japan 81,000 tons. Of its allotted tonnage, the United States had already consumed 66,000 in the Lexington and Saratoga. Only 69,000 tons remained for future construction. The Navy gave much thought and study to the means of best utilising this remainder and, in 1927, when drawing up a five-year shipbuilding program, the General Board recommended construction of a 13,800-ton carrier each year.

The program involving this plan was promptly submitted to the President who approved it on 31 December 1927. It was subsequently submitted to Congress which, by act of 13 February 1929, authorised construction of one 13,800-ton carrier. The Navy attempted in the following years to obtain authorisation for construction of the visualised sister ships, but without success. Indeed, before another carrier was to be authorised, the Navy had become more interested in larger ships of about 20,000 tons.

Small carriers vs big?

In addition to the legal reasons that led the Navy to seek a 13,800-ton carrier, there was a body of thinking on the part of some naval aviators which recognised the utility of small carriers. This was evident as early as 1925 when the General Board briefly considered but rejected the conversion of 10,000-ton cruisers to light carriers.

Two years later, LCDR Bruce G. Leighton, then aide to the Secretary of the Navy, prepared a study on possible uses of small carriers. In addition to protection of the battle line, he suggested their suitability for anti-submarine warfare, reconnaissance, and reduction of enemy shore bases.

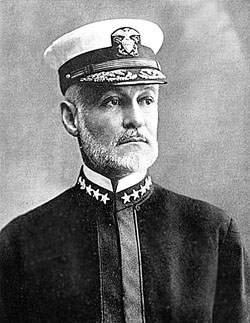

Theoretician VADM (later ADML) Williams S. Sims (left) and the “Air Admiral”, RADM William Moffett, were seminal figures in the development of USN naval aviation.

At about the same time, RADM William A. Moffett argued that British and Japanese experience with small carriers had made it clear that such ships could keep more aircraft in operation than could an equal tonnage devoted to larger ships.

Fleet commanders, who might be expected to have had a more conservative view of the military utility of aircraft than did Moffett and Leighton, expounded concepts that provided further justification for smaller carriers.

Fleet handicapped

For example, the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, noted in his 1927 annual report that the Fleet was seriously handicapped by the absence of a carrier with the battle line upon which spotting planes could land. Thus, both the aviation protagonists and the surface commanders recognised the need for carriers that would perform important roles, even if they were not of a size approaching that of the giants, USS Lexington and USS Saratoga.

Such considerations were in the genesis of CV-4. When it came to reducing them to detailed plans for construction of a new ship, very little had been done. Studies made in 1923 and 1924 had been concerned with island-type vessels such as the Lexington and Saratoga, and were not directly applicable to a new design, which was to be of the flush-deck variety. In addition, the basic concept for CV-4 was embodied in the General Board recommendations of 1927 and predated the commissioning of “Lex” and “Sara”. Hence, the concept could not incorporate any lessons learned during their early fleet operations.

This concept, as outlined by the General Board, included a speed of 29.4 knots, a clear flying deck, 12 five-inch anti-aircraft guns and as many machine guns as possible. On 26 July 1928, the USN Bureau of Aeronautics (BUAER) elaborated on this proposed design in a letter to Commander Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet. The flight deck was to be about 86 feet by 750 feet and fitted with arresting gear. The navigating and signal bridges were to be under the flight deck, well forward, with extensions beyond the ship’s side, port and starboard.

As for the anti-aircraft battery, it had been reduced to eight 5-inch/25calibre guns located two on each quarter. Anti-aircraft battery directors were to be provided, but BUAER thought that range finders should be omitted.

Secondary conning stations were to be located on the starboard side of the upper deck and combined with the aviation control station. A plotting station consisting of flag plot and aviation intelligence office was also to be provided.

Lex, Sara comments

Despite the fact that the general concept could not benefit from experiences of the Lexington and Saratoga, the two ships did comment on plans for the Ranger on the basis of such experience as they had obtained during the first year’s operation. For example, they felt that both elevators and workshop provisions should receive special consideration above and beyond that which had already been given.

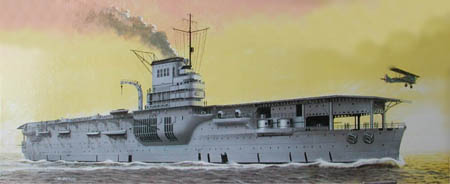

The 14,500-ton USS Ranger (CV-4) at her launch in 1933 (left) and sailing into harm’s way in 1942. She was initially fitted out with an emergency bow arrester wire, a small island and six hinged funnels.

Saratoga‘s commanding officer wrote:

Experience during the present concentration on both carriers has emphasised the importance of the after elevator in addition to the two now contemplated (for CV-4).

There is required a great deal of re-spotting of planes in flight operations, and an after elevator will considerably expedite this process. After planes have landed on deck, it is sometimes necessary to send below a plane from the after part of the flight deck, which is now difficult with the flight deck filled with planes and the elevators forward.

Officers aboard both Lex and Sara held informal conferences, the results of which were passed to BUAER. Speed was most desirable in aircraft carriers, but speed also had its drawbacks, as these officers were quick to point out to their superiors.

The designs of lifts and hangars were no simple matters. Ranging and stowing aircraft require careful planning. In this layout, Boeing F3B-1s of VB-2 Squadron are jammed wing-overlapped in Lexington‘s hangar. If the only serviceable aircraft are in the middle of the stack, it becomes a major operation to extract them for flying.

Workshop vibrations

BUAER informed the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BUC&R): The location of the A&R and general workshops aft is decidedly undesirable and it is strongly recommended that they be relocated further forward, if there is any possible way of doing so. Experience on CV-2 and CV-3 has shown that it is impossible to do any work requiring precision or accuracy, such as cutting a thread, when the ship is steaming at about 22 knots or more.

Early in the planning stage, BUAER encountered head-on the problem of lighting and night landings. A memorandum written for BUAER files dated 14 June 1929 pointed out:

The primary difficulty involved in night operations for airplane carriers is the provision of adequate illumination to enable the pilots to make safe landings and at the same time to enable the ship to maintain darkened ship conditions that will prevent disclosure of the carrier’s provision to surface craft and enemy aircraft. The technical difficulties in this project are so great that complete success can scarcely be hoped for for several years and then not without the expenditure of much more time and effort than appears desirable at present.

Night flying experiments were conducted on the Langley to determine the type of illuminating equipment for the Saratoga and Lexington. Although the number of landings made was not very great, enough information was obtained to determine upon equipment that would at least provide for a point of departure for future experiments in an effort to further solve the basic problem. No carrier night flying has been conducted since 1925.

Intensive experiments

This sparked an intensive series of experiments which caused the introduction of several lighting systems aboard various carriers. At best, most of these provided safe illumination for night landing but were less successful in maintaining a darkened ship. Incandescent lights of low wattage were tested in various arrangements and intensities. Neon tubes were tried, some coloured green, red, blue or amber. Of these, plain white was considered the best—but was not a solution. Even luminous paint was investigated. The problem of night deck illumination was to plague the Navy for years to come.

More light less fright at night

How the problem was handled in USS Ranger is indicated by a November 1934 report her commanding officer made to BUAER:

In anything but bright moonlight when the ship’s outline can be made out at a reasonable approach distance, it is very difficult, definitely too difficult, to get in the groove when only landing deck lights are used. Although Ranger’s landing deck lights extend the length of the ship and are well lined up on each side, which it was hoped would improve the difficulty described by SaratogaLexington pilots, the pilot is frequently too near the ship before he can find out which way to swerve. If he happens to hit the groove early, he is well fixed. If he doesn’t, he sees a jumble of landing deck lights and can only guess whether to change course to right or to left.

With ramp lights turned on in addition to the landing deck lights, there is unanimous agreement that getting in the groove is very easy. Exactly why this is true is not clear, but the string of lights across the ramp appears not only definitely to locate the end of the deck, but also to give the pilot sufficient basis for setting his course normal to the lights and up to the centreline of the deck.

Athwartships landing deck lights at bow and stern are no use and would be hazardous if opened when planes are landing. (Confusion in getting in the groove existed whether or not these lights were opened, worse when opened.)

Other problems were of concern to BUAER during the design stage of CV-4. Relatively minor, but illustrative of the care devoted to carrier design, was the question of paint colour for interior surfaces. A flurry of correspondence between BUAER and BUC&R concerned the colour of paint to use on the deck, overhead, and bulkheads of the hangar.

This was not so much a problem of habitability as it was one of weight limitation and maximum reflective power. White paint, light gray and aluminium were considered. Misinformation supplied to the Bureau of Engineering caused it to advocate light gray, but BUAER objected. Tests were conducted and aluminium proved the lighter and more reflective of the three paints considered.

Finally, in early December 1929, plans for the new CV-4 received approval.

Meanwhile, the Japanese were experimenting with aircraft carrier design. HIJMS Ryujo (Prancing Dragon) was an experimental type laid down in 1929 as an 8000-ton vessel and launched in 1934. Designed with a two-story hangar to carry 48 aircraft, her maximum speed was 29 knots. Stability and sea-keeping qualities were improved by extensive modifications in the mid-1930s. By 1942, after further sea-keeping modifications that included raising her forecastle one deck, and carrying her war complement, her war load displacement exceeded 12,000 tons. She was lost 7 August 1942 to aircraft from the USS Saratoga while supporting a Guadalcanal reinforcements convoy.

Copies were sent to the Fleet, noting that major changes could not be made in them, but that the Bureau would “be glad to have comment or suggestion with regard to minor points, should such comment appear desirable.”

By February 1930, active work on the design of the 13,800-ton carrier had stopped. Shortly after British Prime Minister Mr. MacDonald visited the United States, the President gave instructions to suspend all work on this ship, pending the outcome of the then projected London conference on naval armament. Months went by, the President was consulted again, and again the Navy was told to do nothing about the ship until the treaty had been ratified.

The treaty was signed in London on 22 April 1930. Ratification of the treaty was advised by the Senate on 21 July 1930, and by the President on the following day.

In the meantime, the Navy Department, Office of the Judge Advocate General, drafted an advertisement which was published when the ratification restriction was lifted. The advertisement invited bids for the construction of CV-4. The bids were opened September 3—and proved to be “bombs.”

All bids submitted far exceeded the appropriation given the Navy for construction of the ship, the lowest bid (by Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co.) exceeding the limit by an estimated $2,160,000.

The four Navy Department bureaus involved in the construction plans, BUC&R, BUAER, BUORD and BUENG, forwarded a joint memorandum to the Secretary of the Navy requesting a 60-day extension of the period before execution of the contract, in order to consider necessary changes in characteristics which would permit construction of the carrier within the cost of the lowest bid.

Plans review

Permission was obtained and the various departments reviewed their requirements. Panels of officer-experts in each were formed to submit recommendations. Out went consideration of an extra elevator. Out went the possibility, at this time, of moving the workshops forward, as Sara and Lex had suggested. Submitting its list of recommended savings, BUAER listed the elimination of catapults, smokestacks on one side, sliding doors for the hangars, securing tracks, and airplane booms and nets, and requested that necessary eliminations be made in that order.

A BUAER memo stated:

This bureau feels that elimination or reduction in the balance of items considered, namely, arresting gear, elevators, or gasoline capacity would seriously affect the characteristics of the ship as an aircraft carrier, and, therefore, urgently recommends against any sacrifice in these items.

The French also launched an aircraft carrier, the Bearn, in 1927. She displaced 28,400 tons and was based on an old converted Normandy class battleship hull. Her maximum speed of 21.5 knots severely limited her utility. Bearn spent most of her useful WW II life ferrying allied aircraft. She was the only French-built aircraft carrier until Clemenceau launched in 1957. France commissioned Dixmude, (ex-HMS Biter, CVE) in 1945 and Arromanches, (ex-British Colossus class CVL) in 1946.

Recommendations

By 2 October the Bureaus had signed another joint letter, addressed to the General Board, listing their recommendations on how to cope with the problem of the elimination of design features. Among other things, Ranger‘s fire control was to be simplified, ammunition storage space was to be reduced, bombing planes were to be substituted for torpedo planes (this eliminated the purchase of torpedoes), deck catapults were to go by the board, as were plane booms and nets. Twenty per cent of the flight deck securing tracks were to be eliminated, as well as housing palisades, and the voice tube system. Finally, the arresting gear system was to be reduced. On November 1, 1930, the contract was signed by Newport News.

Throughout official correspondence, the 13,800-ton carrier was referred to simply as CV-4. On December 10, 1930, the Bureau of Navigation informed a long list of addressees that “The Secretary of the Navy has assigned the name Ranger to Aircraft Carrier No. 4, authorised by Act of Congress dated 13 February 1929. The assignment of the name Ranger is in accordance with the Department’s policy of giving names formerly assigned to those battlecruisers scrapped by terms of the Washington Treaty.”

On 26 September 1931, Ranger‘s keel was laid. Seventeen months later, the ship was launched, and she was commissioned on 4 June 1934. Though planned originally as a 13,800 ton aircraft carrier, she exceeded this tonnage by 700 tons. Original plans also called for a severe flush deck, but upon commissioning, she had a small island.

USS Ranger had eight 5-inch 25 calibre AA guns and other AA guns in galleries. She could operate 75 aircraft and had a complement of 1788, of whom 162 were commissioned officers. Her aircraft consisted of four squadrons of bombers and fighters and a few amphibians. CV-4 also was equipped with a box arresting gear, a feature included in other fast carriers until early 1943.

Minimum effective size

The General Board had become convinced, even before the Ranger was launched, that the minimum effective size of aircraft carriers was 20,000 tons. A request for two of these heavier ships was made in the Building Program for 1934, which was issued in September 1932. In May the following year, the Board again submitted this recommendation. As a result, the Secretary of the Navy asked the President for Public Works Administration funds to build two carriers of this tonnage, in addition to other ships. USS Yorktown (CV-5) and USS Enterprise (CV-6) were authorised. Files of the Bureau of Aeronautics housed in the National Archives reveal a memorandum dated 15 May 1931, which was to affect the two new carriers:

The Department has approved a new building program with two aircraft carriers similar to the Ranger, but before embarking on this new construction, it is suggested that a careful examination may show many design changes are desirable.

The particular improvements in the Ranger design that should be considered are: speed increase to 32.5 knots; addition of underwater subdivision to resist torpedo and bomb explosions; horizontal protective deck over machinery, magazines and aircraft fuel tanks; improvement in operational facility (this includes hangar deck devoted exclusively to plane stowage, four fast elevators, complete bomb handling facilities, possible use of two flying-off decks, and improved machine gun anti-aircraft defence).

The British were also sometimes deliberate with their carrier construction program. HMS Glorious, for instance, took six years, from 1924 to 1930, to convert from a 4 x 15-inch “light cruiser” to a 26,500-ton aircraft carrier. After operating frequently as an aircraft ferry, eight hookless RAF Hurricanes flew aboard, during the (arctic) night of 7/8 June 1940, during the evacuation of Norway by British forces. Sailing alone with only two destroyer escorts, despite an available larger covering force, Glorious and the destroyers were surprised and sunk with the loss of 1519 lives in 70 minutes by the two German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on 8 June 1940. There were only 45 survivors. (See the book review, HMS Glorious.)

The Yorktown was launched 4 April 1936, sponsored by Mrs Franklin D. Roosevelt. When the carrier was commissioned 30 September 1937, her overall length was 252 metres (827 feet), beam was 29 metres (95 feet), and standard displacement 19,800 tons. Her trial speed was 33.6 knots.

USS Enterprise (CV-6) was the seventh Navy ship to bear this name. Her keel was laid 16 July 1934 and she was launched 3 October 1936, sponsored by Mrs Claude A. Swanson, wife of the Secretary of the Navy. She was placed in commission at Norfolk on 12 May 1938. Her specifications were similar to Yorktown‘s. She had accommodation for 82 ship’s company officers and 1447 enlisted men.

As soon as CV-5 and CV-6 were authorised, the General Board did not request additional carriers of such tonnage but vainly pleaded for a 15,200-ton replacement for the obsolete Langley. The Langley had been classed as an experimental ship and did not figure in the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carrier tonnage limitations. To replace her with another carrier would have been to violate the treaty. The Navy did plan, however, to request new aircraft carriers when the Lexington and Saratoga reached retirement age.

Tightening tensions

Tightening world tensions in 1938 caused the Navy Department to reconsider its carrier-building program, and the USS Hornet (CV-8) was authorised on 17 May that year. She was launched 14 December 1940 and commissioned 21 October 1941, with CAPT Marc A. Mitscher, her first commanding officer.

USS Wasp (CV-7) commissioned in 1940 and displaced 19,000 tons with a full war load. Her six boilers and two turbines developed 75,000 hp, giving a maximum speed of 29.5 knots. After ferrying aircraft, chiefly to Malta, and incidentally recovering a hookless Spitfire 9 May 1942, Wasp moved to the Pacific, where she quickly established an enviable record. On 15 September 1942, in one of the most productive torpedo salvos ever fired, the Japanese submarine I-19 launched six torpedoes. Three hit Wasp and sank her, one damaged the battleship USS North Carolina, and one sank the destroyer USS O’Brien.

USS Wasp (CV-7) had been ordered earlier, on 27 March 1934. Her keel was laid 1 April 1936, she was launched 4 April 1939 and commissioned 25 April 1940. This carrier had to be built within what was left of the 135,000-ton limit set by the treaty. She was commissioned at 14,700 tons. Thus there were left only a few hundred tons remaining of the treaty-authorised carrier strength.

Already in the mill, during construction of Yorktown and Enterprise, were plans for a new class of aircraft carrier, the first of which would be known as USS Essex (CV-9).

War clouds were gathering over Europe and the Pacific. Fleet exercises and war games were stepped up as international tensions mounted. The treaties of 1922 and 1930 terminated 31 December 1936 when Japan abrogated.

Naval Expansion Act

In its provisions for Naval Aviation, the Naval Expansion Act of 17 May1938 authorised an increase in total tonnage of under-age naval vessels amounting to 40,000 tons for aircraft carriers, and also authorised the President to increase the number of naval aircraft to “not less than” 3000. Carriers built as a result of this authorisation were the Hornet and Essex.

On 8 September 1939, President Roosevelt proclaimed the existence of a limited national emergency and directed measures for strengthening national defences within the limits of peacetime authorisation. In May 1941, an unlimited national emergency was declared. Seven months later Japanese aircraft, launched from carriers, attacked Pearl Harbour, and within 24 hours, the President went before Congress and the nation was at war.