Museum of Anthropology, UBC

The Museum of Anthropology in the University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, Canada has by far the best collection of original totem poles and other carvings by the Northwest First Nations people. The exhibits are not only more numerous but are in better condition that those found, for instance, in totem pole dedicated areas, such as Thunderbird Park in Victoria, BC, and even the National Historic Park in Sitka, Alaska.

Detailed knowledge

As a bonus, the university lecturer, who guided the afternoon tour during a recent visit, had an amazingly detailed fund of both local and academic knowledge. His discussions linked the totemic sculptures to important scientific studies. A systematic study of them and their associated culture contributed to Franz Boas constructing the scientific underpinnings for what became known as the science of anthropology in the late 19th century. At a time when theories of inferior/superior race, culture and art pervaded both academia and politics, it was Boas and his Columbia University colleagues, like Margaret Mead and Bronislaw Malenowsky, who turned those poisonous positions on their collective heads.

Instead of cephalic indexes, phrenology, language complexity, written records, skin colour and other so-called immutable measures of race “purity” and “superiority”, Boas extended Darwin’s work on evolution. He was well ahead of later DNA research that found all human beings sharing very much the same genetic make-up and therefore intuitive behaviour. The Boas group claimed furthermore that there were only comparatively minor behavioural variations that were probably as great within “racial groups” as between “racial groups”.

Therefore it was the environment (nurture), and not genetics (nature), that shaped the most important aspects of human behaviour. At great personal risk from fascist thugs and contrary to Nazi ideology, Boas, debunked the great Aryan race superiority myth using, in no small part, hard observational data collected from his original Northwest Indians studies.

Eugenics irrelevancies

Basically, Boas and his colleagues quietly but convincingly proved that despite cosmetic irrelevancies such as skin colour or eye shape, all human beings belonged to one “race”. Moreover, despite strong claims to the contrary, there was no such thing as “good art” or “bad art” or other popular measure that would allow one culture to claim superiority over another. They convincingly argued that all science could do was to describe the cultural and environmental contexts of various people groups.

Good science might well breed a marginally faster racehorse but, apart from its abhorrent moral overtones, the so-called science of eugenics will never produce important change or guarantee the “purity” of a “race” of human beings. The popular milestones of culture, like written language and scientific advancement, were largely irrelevant in environments that did not support such culture. Boas demonstrated that instead of written texts, the Northwest Indians recorded all their important cultural history in other ways, such as complex songs, poems and sculpture.

Religious zealots

Within that context, the UBC’s totem poles are important and highly valuable cultural descriptive measures that were very nearly destroyed. Their complexity and the creation stories they described were almost lost when government-sponsored Christian missionaries imposed their own creation theories, chiefly in the 19th century. Christian zealots routinely denigrated and destroyed their priest-shamans, totem poles and other religious artefacts.

Paradoxically, other material was destroyed by the native people themselves during the potlatch ceremonies that the missionaries and government worked so hard to suppress. These interventions, together with introduced diseases, led to a massive identity crisis within the culture that persists today. Similar cultural conflicts may be seen in Australian Aborigines.

The few totem poles and other artefacts that remain today are precious because they help to preserve the cultural remnants of a once-great group of nations. Those at UBC range from ancient weather-beaten fragments to modern replicas. One striking modern carving is Bill Reid’s sculpture of The Raven and the First Men.

Trickster Raven

Bill Reid was a newsreader for the Canadian Broadcasting Commission when he retired in 1958 to become a full time artist and sculptor. Reid carved the Museum’s striking raven statue from a single massive block of 106 laminated yellow cedar pieces. It represents the Haida creation myth about a huge raven finding this large clam shell after the creation flood. There were baby men inside who were reluctant to come out until persuaded by the trickster Raven. The men went on to find other clam shells, from which they released women. Thus, the human race started. Reid also contributed a large number of other important works to the museum. There are about 6000 local-area Indian artefacts within a total of about 13,000 objects on display in the museum. These include jewellery, baskets and other woven craft, as well as a small number of dugout canoes.

These boats, between three and 20 metres long, are interesting. They were typically carved from a single cedar log, but to establish their final form they might be filled with water into which hot rocks would be loaded until the wood became pliable enough for it to be shaped. Then the larger canoes might be intricately decorated with totemic and other markings. Most of these fine boats were used for fishing and local transport, but some ocean-going vessels were fitted with woven sails and used for long distance trading and raiding 500 miles or more away.

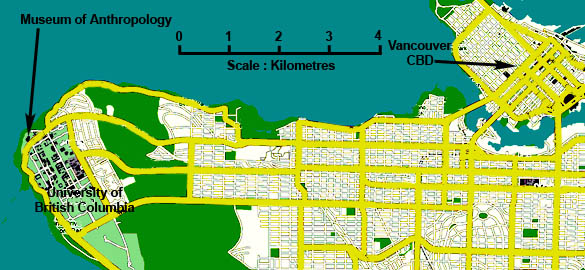

It’s a 20-minute bus ride from Vancouver to the museum.

The museum is at 6393 NW Marine Dr, a $1.50 (seniors), 20-minute bus ride from downtown Vancouver. One option then is to walk 10 or 15 minutes from a turn-off before reaching the terminus (ask the driver). Museum entry costs $7.00 (seniors) and further detailed information, particularly opening times, may be found at www.moa.ubc.ca. It is a rare cultural gem well worth visiting. Many will agree that the Trickster Raven statue alone might well be worth the trip.