USN Carrier Evolution V: War Games 1

By Scot MacDonald. Fifth article in a series. Reprinted with permission: Naval Aviation News August 1962 pp. 28-33.

One of those whose untiring efforts helped shape the evolution of the “all big gun battleship,” ADML William S. Sims, did not immediately endorse Naval Aviation—especially ships carrying naval aircraft—upon its introduction as a weapon in the country’s arsenal. In 1909, for instance, he wrote: “According to the papers, one of the Wright brothers has stated that it would be impracticable to hit anything by dropping a projectile from his flying (machine). That Wright man is right, all right.” Sims had a deep appreciation and understanding of the merits of the battleship as a weapon system whose evolution he had fought to promote and he was not about to write it off, except on the basis of sound evidence.

During WW I and the years immediately preceding it, aircraft design improved spectacularly. By the end of the war the U.S. Navy still did not have an aircraft carrier. His observation of the limited use of such ships permitted him to state with justification, “All the aeroplane-carrying ships in the world could not make an attack upon a foreign country unless they were supported by a battleship force that was superior to that of the enemy.”

Build carriers, “the battleship is dead”

Not until the end of the war, when VADM Sims assumed leadership of the Naval War College at Newport, did his thinking undergo a profound change. At the game board there in 1921, he recognised not only the advantages and potentials of airpower but also the brevity of the future of battleships. “If I had my way,” he said, “I would arrest the building of great battleships and put money into the development of the new devices and not wait to see what other countries are doing.”

By March 1922, after witnessing the 1921 bombing tests off the Virginia Capes, he had written, “The battleship is dead.”

During Sims’ tenure at the War College, the Navy Department inaugurated a series of war games, fleet exercises, that were conducted during the next two decades. Through these Problems, the Navy obtained practical experience in testing the “new devices” under simulated combat conditions.

Naval Aviation had entered fleet manoeuvres as early as the winter of 1912-13 when the entire aviation element—pilots, student pilots, enlisted men and aircraft inventory (which then totalled five planes)—was transported to Guantanamo Bay to take part in planned exercises. From their camp at Fisherman’s Point where the present air station is located, they worked to achieve three goals: first, to prove the utility of the airplane as a scout under simulated war conditions; second, to test its usefulness in detecting mines and submerged submarines; and third, to stimulate interest in aviation among officers in the fleet.

Veracruz action, 1914

Naval Aviation next joined the fleet in 1914, in connection with actual hostilities in Mexico. At that time, an A-3 and a C-3, put aboard the Mississippi, saw action at Veracruz. Daily reconnaissance flights kept landing forces informed of the enemy dispositions inshore.

(Three planes placed aboard the Birmingham were taken to Tampico but did not see action.)

This Curtiss C-3 “hydroaeroplane”, based in USS Mississippi (BB 23) and flown by LTJG (later VADM) P.N.L. Bellinger, was the first U.S. naval aircraft to see active service. Bellinger overflew Veracruz, Mexico, on 25 April, 1915, searching for enemy positions and mines. On 6 May, he became the first USN pilot to report damage by hostile fire (small arms) during another reconnaissance mission.

As a result of the experience at Veracruz, Naval Aviators judged the hydro-aeroplane more efficient than the flying boat type then in use. Recommendations were also made on the design of aircraft.

(Ed. note: There was considerable interchange, leading to confusion, but the term “hydro-aeroplane” gradually evolved into “seaplane” and craft such as the Curtiss C-3 became known as “flying boats”.)

Extraordinary expansion

The Navy’s air arm was still very small when the United States entered WW I. In the next year, seven months and four days, while war raged, its growth was extraordinary. By the time the Armistice was signed, the Navy had 2107 planes, 570 of which were overseas, 15 dirigibles, 205 kite balloons and 10 free balloons.

Thirteen bases were established in the U.S. and the Canal Zone, only one of which, at Galveston, was not yet in operation. In Ireland, the Navy had four seaplane stations, one kite balloon station, a receiving station and a supply station. Two stations, including a major assembly and repair base, were established at Eastleigh, England. Two more stations and a training school were built in Italy. There were 18 stations in France, including an assembly and repair base at Pauillac and a school at Moutchic. Additionally, the Navy had a base operating in the Azores, one in Canada, and a rest station in the British West Indies. There were fewer than 300 officers and men in Naval Aviation when the war started in April 1917. At war’s end, in November 1918, there were 39,871, of whom 19,455 were abroad.

Flying boats, such as this WW I-era Curtiss H-16, provided the majority of the air component in USN fleet war games immediately after WW I. The H-16, built in the USA, was a derivative of a joint British/American project, the Felixstowe. The 29 x 14.1 x 5.4 metres craft had two Liberty 400 hp engines and a crew of four. It could carry five Lewis machine guns and four 104 kg bombs.

Naval air operations in this war were predominantly in support of allied shipping, launching aircraft from land bases for anti-submarine patrols. It was not until the years immediately following the war that the U.S. Navy returned to the theory of integrating aviation with the Fleet. Although aviation had proven itself, there was still resistance within the fleet toward the imminent merger. A CNO newsletter of July 30, 1919 carried a report on Fleet Air Operations:

Early in January 1919, it was decided to send a detachment of six H-16 flying boats to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to operate with the U.S. Fleet for the purpose of proving to it the use of aircraft in actual naval operations and of demonstrating the practicability of maintaining an air detachment with the fleet. It was accordingly decided to operate these flying boats from moorings and to quarter the aviation personnel on a ship carrying necessary repair personnel, necessary spare material, etc., for the upkeep of the squadron.

In addition to the six flying boats there was also an airplane division consisting of two Sopwith Camels and [a Sopwith] 1½ Strutter on board the USS Texas under the command of LCDR E. O. McConnell, USN.

Not once when the air detachment was called upon to send machines for operations with the fleet has it failed to send them, and not once when machines have been sent on a certain mission has the air detachment failed to accomplish that mission. This has required flying in all sorts and conditions of weather, high winds, rain, fog, and low visibility. It has required duty in spotting, bombing, scouting, passenger carrying, mail carrying, and all types of work which aircraft with the Navy can be called upon to do.

The air detachment also had a kite balloon division and the report ends with an optimistic, though probably inaccurate, note: The result has been that the officers of the seagoing Navy have been converted to the belief that aircraft are practicable and essential to a well rounded fleet.

Numerous training periods and exercises were conducted subsequently, in which aviation participated with the fleet, but it was with the annual Fleet Problem of the twenties and thirties that these manoeuvres were conducted on the largest scale.

Historian observation, analytical study

Historian LCDR James M. Grimes, USNR, said:

Taking an ever increasing role in these problems, Naval Aviation gradually developed and came of age. The Fleet Problem, therefore, serves as the measuring rod for this growth to maturity. It provides an annual check on what Naval Aviation was accomplishing and the reports and recommendations which grew out of each problem show how important the problems and their results were in development of aviation in the Navy.

A study of these problems can be made successfully by breaking them down into five groups, studying each to determine tactics employed and lessons learned. Basically, these groups are:

1. The days of the “constructive” (paper) carriers, when other ship types were designated aircraft carriers because of unavailability of the real thing.

2. The period when the USS Langley, a converted collier, joined the games as the only aircraft carrier in the U.S. Fleet.

3. The profound effects on tactical thought precipitated by entry of the USS Saratoga and USS Lexington into the games.

4. The addition of the USS Ranger, and

5. The years immediately prior to WW II when the U.S.Navy operated five aircraft carriers.

Fleet Problem I: 1923

The first of the Fleet Problems occurred in 1923, in the Panama-Pacific area. It was a resounding success for the Black Fleet, given the mission attacking the defences of the Panama Canal, and a shattering failure for the Blue, assigned the defence of the Canal.

Blue’s air forces consisted of the tenders Wright, Sandpiper and Teal, and the 18 patrol planes of Scouting Plane Squadron One (half the planes were based at Ballena Bay with the Sandpiper and Teal, the remaining at Bahia Honda with the Wright), the patrol planes based at Coco Solo and all the available Army planes.

The Black Fleet was assigned the battleships New York and Oklahoma as “constructive” carriers.

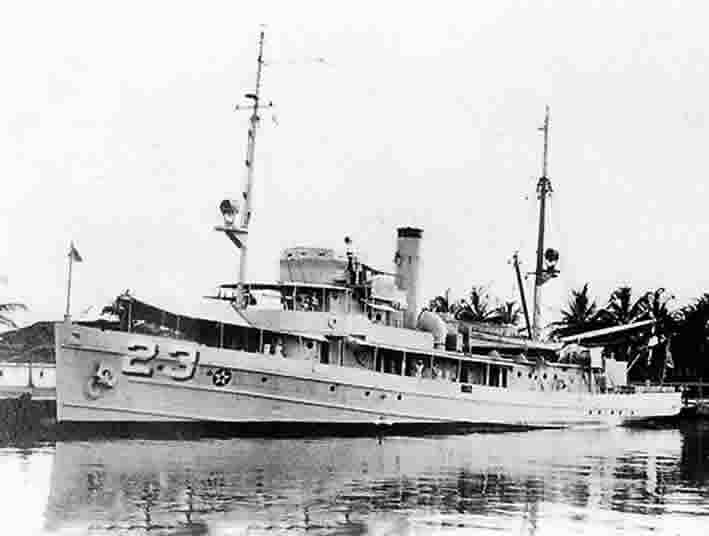

USS Wright (AZ-1, left) was commissioned as an airship tender but employed mainly as a seaplane tender. She displaced 11,500 tons on a 136.5 x 17.7 x 7 metres hull and had a maximum speed of 15 knots. Her 228 crew also manned her two 127 mm (five-inch) and two 76.2 ( three-inch) guns. USS Teal (AM-23), like Sandpiper (AM-51) was a converted minesweeper displacing 840-950 tons.

Approaching the Canal, one of the battleship “carriers,” the Oklahoma, launched a seaplane by catapult to scout ahead of the force. Early the next morning, a single plane representing an air group took off from Naranyas Cays, approached the Canal from seaward, flew over Gatun Spillway, and dropped ten miniature bombs. This plane completed its mission undetected and theoretically destroyed the Spillway.

An official report submitted after the problem pointed up the susceptibility of vital parts of the Canal to destruction by air. The report urged, among other things, that air defences of the Canal be strengthened and that rapid completion of aircraft carriers be effected for offensive and scouting purposes.

Fleet Problem V: 1925

Naval Aviation played little part in the next three exercises. It was not until Fleet Problem V in March 1925 that USS Langley entered exercises off the California coast. The second phase of the problems began; a new element was introduced.

USS Langley (CV-1) seen here in 1928, was the first, and for many years the only, aircraft carrier to participate in US war games.

Basically, the supposition for this problem was that strained relations existed between Blue (the U.S.) and Black, an imaginary country in the area of the Hawaiian Islands. When Black declared war, its Commander-in-Chief was ordered to Guadalupe Island where he was to occupy an unfortified anchorage from which he was to operate against Blue in the Eastern Pacific.

Langley BZ

Black was given the Langley and the tenders Aroostook and Gannet, as well as planes based aboard battleships and cruisers.

The Blue force was considerably smaller, having only 15 cruiser-based planes and two other aircraft based on the Wyoming. Planes aboard the Wyoming were useless, however, for the battleship was not equipped with a catapult. Grimes records:

The Black War Diary shows that the greatest part of the air activity during Fleet Problem V was centred around the Langley. Scouting flights were conducted each day as the Black Fleet proceeded towards Guadalupe. The largest number of planes used at any one time was ten. The duration of these flights ranged from 30 minutes to two hours.

On the last day before the arrival at Guadalupe, the Langley received a ‘well done’ for the feat of launching ten planes in 13 minutes! None of these flights resulted in contacts.

On March 10, the Langley was ordered to have her planes ready for an 0530 takeoff the next morning. These planes were to make an aerial reconnaissance flight over the anchorage before the Black Fleet entered. This operation never took place, the Problem being terminated at 0508 March 11 by the Chief 0bserver.

Introduction of the Langley to fleet operations was considered a valuable experience. As a result of this problem, the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, recommended that the Saratoga and Lexington be completed as quickly as possible. He also urged that steps be taken to ensure the development of planes of greater durability, dependability and radius, and that catapult and recovery gear aboard cruisers and battleships be further improved.

Fleet Problem VI: 1926

Details concerning Fleet Problem VI, conducted in 1926, are unavailable. Pertinent documents on orders, instructions and operation reports are lost. It is known, however, through the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1926, that a combined U.S. Fleet participated in a joint Army-Navy minor problem and conducted “strategical and tactical exercises in the vicinity of the Canal Zone until the middle of March 1926.”

Fleet Problem VI was conducted during this period.

Just before Fleet Problem VII got underway in 1927, a joint Army-Navy exercise was conducted, again testing defences of the Panama Canal. USS Langley provided defence against attacks on ships by land-based Army planes and was also used for spotting submarines. This exercise marks the first time an aircraft carrier was used to protect ships of the line. Battleship-based planes were used for spotting during bombardment of the Canal installations.

Canal defences were again found weak, but again, “constructive” planes were used in the attacks. In each of the two attacks on Miraflores Locks, only one plane was launched; it represented the attacking forces. This was not considered an effective test. Grimes noted: “In later problems when carriers were available from which attacks in force could be launched and greater reality could be introduced into manoeuvres, the vital necessity for air defence of the Canal was to become even more apparent.”

Fleet Problem VII: 1927

The seventh Fleet Problem provided more experience in carrier operations. Conducted in the Caribbean in March, Blue Fleet was given the task of escorting a large, slow, overseas convoy and was then to establish a base under enemy opposition. This fleet was then to oppose the Black Naval Force from that base. Black’s mission was to provide search and contact scouting, track submarines, and attack a large convoy accompanied by a strong escort. The Langley was assigned to the Blue Force. Again, the converted collier-made-carrier was to provide protection for ships of the line.

A Vought VE-7 Bluebird fighter traps aboard USS Langley in 1927. This aircraft is interesting because it has an arrestor hook to catch an athwartships wire and tiny hooks between the main wheels to catch longitudinal wires. It also sports a British-designed “hydrovane” immediately forward of the main axle, theoretically resisting the tendency of the aircraft to nose over when ditching, but perhaps having an opposite effect in most sea states. The Bluebird was designed as a two-seat Army trainer, but the single-seat version performed better than many contemporary American fighters.

On the last day of the game, Black conducted a surprise air attack—delivered by 25 land-based aircraft (from Mole St. Nicholas, Haiti)—against the Blue Force. Shortly before this, Langley maintained a protective air patrol over the convoy, but discontinued it hours before the attack was pressed home. Caught unawares, Langley‘s planes were no help.

Even though the problem had officially terminated by the time Black’s aircraft reached Blue’s ships, observers considered the attack successful, though the Commander-in-Chief deplored the clumsy formation of the attacking planes.

One of the most revealing outcomes of this problem was the need to allow aircraft carriers greater latitude in manoeuvring, as dictated by weather and the position of the enemy forces. Commander, Air Squadrons, also felt that he should have complete freedom of action in employing carrier-based aircraft in order to get maximum efficiency in air operations.

Fleet Problems VIII and IX: 1928 and 1929

Fleet Problem VIII, conducted in the Hawaiian-Pacific area in April 1928, provided further experience in aircraft carrier operations and scouting patrols, Langley, Aroostook and Gannet again participated and again air operations were limited to scouting. Bad weather and heavy seas effectively limited air operations, but despite uncooperative weather, Commander-in-Chief, Battle Fleet, noted that a sufficient number of aircraft were launched from the Langley “to show that the use of planes from carriers for all contemplated operations is both practicable and feasible.”

USS Lexington launches a Martin T4M-1 torpedo bomber in 1929.

Of all the Fleet Problems conducted before 1940, the next, Fleet Problem IX, undoubtedly received the most publicity. Conducted in 1929, it saw the introduction of the world’s largest aircraft carriers, the Saratoga and Lexington. The problems entered their third phase. “The experience gained and the conclusions drawn,” says historian Grimes of this problem, “had a marked influence on the development of fleet tactics and strategy in general, and on Naval Aviation in particular.”

The Panama Canal was again chosen for the critical area under hypothetical attack. Previous exercises indicated a major weakness in defence of the Canal, protection from air attack, but this problem was to test the conclusions reached in the past by providing actual aircraft carriers and full strengths of aircraft.

The problem assumed that a war had existed between Blue (the U.S.) and two enemy nations, Black (in the Pacific) and Brown (in the Atlantic). In airpower, Blue was assigned the Lexington, 145 naval aircraft, and the cooperation of the U.S. Army in the Canal Zone and 37 planes based there. Black was given the Saratoga and the Langley. When it became evident that Langley would not complete her overhaul in time for the games, the tender Aroostook was substituted, the single amphibian aboard representing Langley‘s 18 fighters and six scouts, though these aircraft were actually transferred to the Sara. The Brown force proved to be a paper power; neither ships, planes, nor personnel were assigned; other than in initial planning and estimates of the situation by Blue and Black, Brown ceased to be a factor in the game.

Destroy Panama Canal

A detachment from the Blue force, including the Lexington, transited to the Pacific side before Black force could launch a surprise attack. On the same day, the remainder of the Blue force was to have left Hampton Roads for the Canal. It was Black’s intent to destroy the Canal before this second detachment could complete the passage.

Blue’s intelligence indicated that Black would attempt an attack on the Pacific side. Actually, Black planned a surprising two-pronged attack. The “squadron” aboard the Aroostook was to make a long-range flight, far beyond capability of return. Its attack was to be made on the Atlantic side, at the conclusion of which, the “planes” were to land and surrender. Simultaneously, Saratoga, accompanied by Omaha, was to attempt a daring tactic: take a wide, two-day swing to the south and then launch carrier-based planes for the Pacific attack. This latter demonstration was to make a profound impression on naval tacticians.

Surface Attack Group

On the morning of January 25, 1929, two days before the Problem was to end, the main Blue force, including the Lexington, came upon Black’s striking force. Black’s Battleship Division Five was steaming downwind while the carrier was steaming up, preparatory to launching her planes for an air attack. The battleships opened fire and, because of the close range, would surely have sunk the Lexington in actual battle. For this carrier, it was a disastrous ending to her first important activity in the problem.

Umpires ruled the carrier “damaged,” however, for the loss of the carrier at this early stage of the game would have had a profound restriction on Blue’s capability during the coming “interesting” part of the problem. Lexington was instead penalized in speed; she was permitted only 18 knots.

The carrier had already launched some planes. After the attack by the battleships, the carrier, running into rain and reduced visibility, was forced to recover these aircraft under very adverse conditions. Noted the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet: “Flight deck personnel and flying personnel alike are deserving of great credit for the manner in which squadrons came aboard on this occasion.”

Sara vs DD

The Saratoga, in the meantime, was steaming south. She was detected by an enemy destroyer upon which she opened her eight-inch guns. This had unfortunate results. The destroyer was “sunk,” but in the process, one of Sara’s planes, a T3M (a Martin torpedo bomber), was literally destroyed.

Spotted in the hangar deck just aft of the forward elevator and 68 feet from the muzzle of the gun, the plane suffered 36 crushed ribs and some torn fabric, directly attributable to the blast from the heavy gun. The eight-inchers were destined to be removed from the Saratoga, but not before WW II.

Later that day, the carrier encountered another Blue ship, the Detroit, which continued to track her through the night, supplying the Blue commander with vital information. The Lexington was ordered to give chase, but because of her reduced speed could not close during the night.

At 0525 the next day, the Chief Observer cancelled this penalty.

USS Detroit (CL-8) shadowed Lady Lex overnight in Fleet Problem IX. She was a fast Omaha class cruiser, mounting ten 152 mm and eight 76 mm guns, six torpedo tubes and two aircraft on a pair of catapults. She had a crew of 458 and displaced 7050 tons on a 167.8 x 16.9 x 6.1 metres hull. Detroit could manage a handy 34 knots.

The 26th was an active day for the Saratoga, and not an altogether lucky one. Near five that morning, while about 145 miles from Panama, she launched an initial attack of 70 planes against the Canal. Her aircraft in the air, the good times were over for the Sara.

Navigation errors

Because of navigational discrepancies, the carrier and the Omaha contacted Blue’s Battleship Division Two instead of her own Battleship Division Five. The carrier was under heavy fire at short range from three of the enemy battleships and was scored a “sinking.” Had she escaped this disaster, four torpedoes “fired” from an enemy submarine at 1200 yards would have hurt her heavily and possibly sunk her. At 0656, Sara launched two more squadrons, at the completion of which she had 83 aircraft in the air.

At 0600 the same day, the Aroostook stopped near Jicaron Island and 17 minutes later her single plane—a Sikorsky amphibian, theoretically representing Langley‘s squadrons—took off to bomb Gatun Locks, Gatun Spillway and Coco Solo.

The commander of the Blue force, though, had committed a blunder by not advising either Coco Solo or the Army of the substitution. The Sikorsky went about its mission of bombing the Atlantic side of the Canal, encountering no opposition. When he completed the job, he landed at the Atlantic terminal of the Canal, surrendered to a stunned “enemy” and confessed his accomplishment.

Saratoga‘s problems were not yet over. Shortly after the Chief Observer lifted the speed limitation from the Lexington, Lex launched her aircraft against her sister ship. The Sara-based planes, returning from a successful raid on Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks and the airfields at Fort Clayton and Albright, were in the process of landing when the Lexington-launched planes arrived on the scene. Sara “went down” for the third time.

Men in the Lexington had little to cheer about, though, on the morning of January 27. Friendly planes of VT-9 (squadron) took off from their moorings at Balboa and stood out to attack the Black carrier and bombarding forces. About 0700 they reached a carrier and started bombing. Later, they learned it was their own ship, the Lexington.

“This error was understandable, in view of the fact that Saratoga and Lexington were operating within 12 miles of each other at that time and it was not possible to distinguish markings, owing to the presence of a large number of men on turret tops. For purposes of identification, each turret top of the Saratoga bore two painted white stripes parallel to the axis of the guns. The turret tops of the Lexington were painted conventional war colour,” observed Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet.

In later years, Saratoga was made more easily recognisable by the painting of a large stripe down the centre of her stack.

Fleet Problem IX marked an outstanding achievement in Naval Aviation.

The Boeing F2B-1 was typical of the early USN carrier-borne fighters, scouts and dive-bombers that flew from USS Lexington and Saratoga in Fleet Problem IX. This aircraft, from the “Tophatters” VB-3 Squadron, was probably based in Saratoga. With a wingspan of 10.3 metres, length 7.1 metres and height 2.4 metres, its Curtiss D-12 radial engine delivered 535 hp, giving it a maximum speed of 138 knots.

It marked the first appearance of modern large carriers with the Fleet in a fleet problem. But the most significant event of this problem, and possibly in any before WW II, was the employment of Saratoga as a separate striking force. Its effect on the future use of carriers was immediate. In the 1930 manoeuvres, a tactical unit, built around the aircraft carrier, appeared in force organization for the first time.

For many historians of naval warfare, Fleet Problem IX marked the introduction of the fast carrier task force. Regardless of its genesis, this tactical weapon was tested and refined during the war games of the Thirties. Addition of the carriers Ranger, Lexington, and Saratoga was to provide more flexibility and realism in future games. A discussion of them, as well as the results of the fleet problems, will be presented in the following chapter describing in detail the evolution of aircraft carriers.