The Rufigi Delta and HMAS Pioneer

HMAS Pioneer, the RAN’s old Pelorus class light cruiser, fired more shots in anger than any other RAN ship in WW I. Most of her angst was directed towards the blockade and destruction of the commerce raider SMS Königsberg and other targets in German East Africa between 6 July 1915 and 22 August 1916, but no Pioneer shell was ever directly aimed at Königsberg herself.

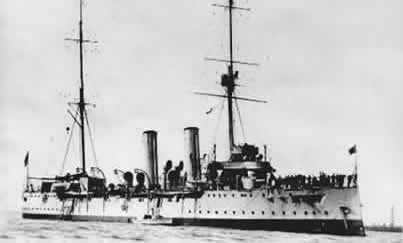

HMAS Pioneer

This is not just a simple history of a boring blockade interspersed with frantic but glorious action, like the Nelson-era sailing ship blockades. Perhaps one of the biggest stories yet to be told was the effort required simply to keep Pioneer going. Like others of her class, Pioneer required not only frequent coaling, but also constant maintenance. These ships had a maximum design speed of 20.5 knots, but were notoriously unreliable. As one commentator said: “By World War One, they were not good for more than 16 knots and often suffered from boiler trouble and mechanical defects,” (Bastock, p 50).

First Naval Gunfire Support

On the other hand, Rufigi was important because this was the first time aircraft had ever been used in support of naval gunfire that had no other means of observing fall of shot, and an Australian ship was there on the spot, so to speak. Königsberg was destroyed by naval gunfire and scuttling charges. Our cruiser remained there, watch on stop on, for most of the blockade from the moment she arrived.

German East Africa, 1914.

When war was declared on 4 August 1914, the near-brand new SMS Königsberg was in East Africa, fresh out from Germany. Her commerce raider sister ship, SMS Emden, was a part of VADM von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron, based at the German colony Tsingtao (now Qingdao), China. Emden was detached with a collier, like Königsberg, to play havoc in the shipping trade routes, initially in the Indian Ocean. The rest of the German East Asia Squadron went on to a brilliant victory on 2 November, 1914, off Coronel, Chile, and near annihilation off the Falklands a month later. About the same time HMAS Sydney caught and destroyed Emden at Cocos, on 9 December 1914.

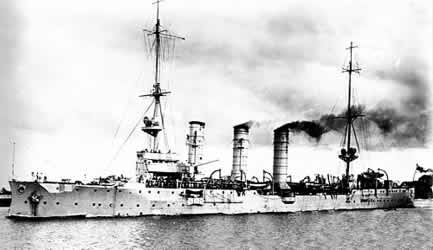

SMS Königsberg.

Königsberg recorded some early notable successes, for instance capturing the first British merchant ship to be lost in the war, the 6600-ton City of Winchester, in the Gulf of Aden, on 6 August 1914. She also destroyed the elderly light cruiser HMS Pegasus, of the same class as Pioneer, in a bold attack on 20 September in Zanzibar Harbour. The German cruiser intended to fight her way back to Germany in time, but she experienced serious problems with a high pressure steam valve (other sources say a broken connecting rod) and retired, around 21 September, to the Rufigi River Delta (in present-day Tanzania, some 70 miles south of Dar-es-Salaam) with her collier Somali and other small craft for repairs. The disease-infested delta was a huge maze of shifting channels and shallow waterways. It was impassable to ocean-going vessels, according to British charts, but a recent survey and local knowledge gave the Germans an edge.

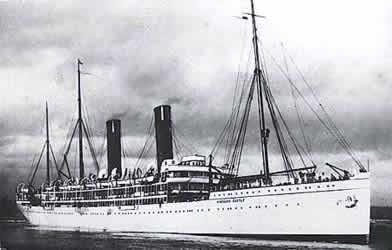

Modern cruiser and armed merchantman cruiser

The modern (in 1915) cruiser HMS Chatham (left, in 1920 livery) and armed cruiser HMS Kinfauns Castle were first on the scene.

When the modern British cruiser HMS Chatham arrived on the scene 30 October, they sighted Somalia‘s topmasts and sent an armed landing party ashore that gained intelligence that a large warship was anchored out of sight some five miles upstream. They also found the whole delta area strongly defended by German and Askari troops and the waters probably mined. Meanwhile, Königsberg‘s defective high pressure steam valve (or connecting rod) had been taken overland, remanufactured in the German Dar-es-Salaam railway workshops and was being reinstalled (Alliston p 26).

Somali destroyed

It did not take long for a motley group of British ships to blockade the delta. On 1 November Chatham fired on the Somali at 14,500 yards and set a blaze that led to the collier’s total loss. Königsberg responded by moving further upstream. The modern cruisers HMS Dartmouth and Weymouth arrived a couple of days later to help seal the delta. The British sank a block ship, the collier Newbridge, across one main channel, but this did not necessarily seal in Königsberg.

The Union Castle liner Kinfauns Castle had been requisitioned by the RN at the outbreak of war and converted into an armed merchant cruiser with eight 4.7-inch (120 cm) guns. In early November she picked up a Curtiss 90 hp Flying Boat Type S and its pilot, Mr H.D. (Dennis) Cutler from Simonstown, South Africa. The British planned that the aircraft would find the Königsberg, then either destroy the anchored ship by bombing or provoke her into sailing into the trap they were setting outside.

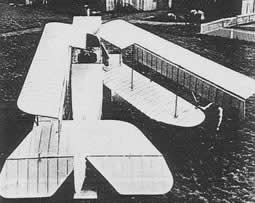

A Curtiss 90 hp flying boat, with Glenn Curtiss (left) and Henry Ford.

The civilian pilot was quickly commissioned as a SBLT RNVR and, helped by MIDN A.N. Gallehawk RNR, worked feverishly to make his machine airworthy. No-one, it seems, was aware of the way tropical heat and humidity affected these aircraft and their engines. The flying boat obstinately refused to get airborne “unless the sea was dead calm” (Alliston p. 33). On 19 November, after a number of test runs and with the aircraft finally stripped to its bare essentials, Cutler staggered off and headed for the coast into monsoonal weather. He had no compass and only an hour’s fuel. He failed to find his target, got lost in cloud and many aboard the ships gave him up for lost when he did not return.

T-model Ford radiator

Fortunately, a local sailing boat reported sighting the aircraft heading south and six hours later launches found Cutler, recovering from a precautionary landing that he made near uninhabited Okusa Island. His aircraft was damaged, but after replacing the radiator with a T- model Ford version fetched by HMS Fox from Mombasa, Cutler repaired it enough for a second try on 22 November. This time he located Königsberg some seven miles upstream, heavily defended and apparently ready to sail should the RN relax the blockade. Unfortunately, he damaged the aircraft’s hull on landing after this sortie, but the boxed parts of another Curtiss had been located in Durban and these were brought up by Kinfauns Castle.

Königsberg‘s upstream position was disputed by the navigators, on shallow water grounds, so Cutler made yet another sortie on 4 December, this time with a CMDR Fitzmaurice as an observer. Fitzmaurice confirmed Königsberg was anchored close to Cutler’s estimated position and well out of cruiser-gun range.

The Curtiss aircraft and its engine were performing so poorly in the tropical conditions that any attempt to bomb the cruiser was out of the question. The leaky wooden hull was waterlogged and the engine could not produce full power, despite replacing parts cannibalised from the second flying boat. On his next flight, 6 December, Cutler was either shot down or had an engine failure about one mile upriver. He swam ashore and was taken prisoner. MIDN Gallehawk, however, lurking nearby in the armed tug Helmuth, drove off eager Askaris who aimed to pull the aircraft ashore. He towed the machine out to sea under heavy fire from the delta river banks but it was all to no avail, because that flying boat never flew again. Cutler spent the next three years as a prisoner and his aircraft was eventually consigned to the Durban Museum.

Sopwith floatplanes

The Admiralty sent two highly reputed Sopwith floatplanes, variants of the 1914 Schneider Trophy-winning Tabloid machine with 100 hp Monsoupape-Gnome rotary engines. They arrived on 21 February 1915, together with a 20-man RNAS party commanded by F/LEUT J.T. Cull. In temperate climes, the aircraft could carry a two-man crew and a useful bombload: two 50 lb (22.7 kg) and four 16 lb (7.3 kg) bombs. This proved impossible in the tropical conditions of the Rufigi Delta and one of the delicate machines was wrecked when the propeller disintegrated during testing. The heat had softened the glue that held the beautifully hand-crafted laminated propeller together. The other machine also fell victim to the climate, with the engine producing nothing like its rated power, even stripped of its cowlings. It took only a few days for the oppressive heat and humidity to warp the wooden frame and propeller out of shape. At best, it was found that the remaining Sopwith could make only 1000 feet altitude, with reduced fuel, no observer and no bombload.

A Sopwith Baby, similar to the floatplanes at Rufigi.

Meanwhile, the old light cruiser HMAS Pioneer, built in 1900 and commissioned into the RAN in 1913, had been patrolling out of Fremantle. She was detailed to escort the first AIF convoy that departed Albany 1 November 1914, but had to withdraw because of condenser problems. At Admiralty’s request, she finally left Fremantle 9 January 1915 to bolster the Rufigi Blockade. On her arrival, the Rufigi force was a “most heterogeneous one,” including “the modern light cruiser Weymouth, the less modern Hyacinth, the Pyramus (sister ship of the Pioneer), the armed liner Kinfauns Castle, four armed whalers, an armed steamer and an armed tug,” said Arthur Jose in his typical understated manner (Jose, p. 234).

RADM King-Hall

Chatham had retired to Bombay to refit and go on to the Mediterranean but RADM King-Hall arrived on 6 March 1915 to take charge in the old battleship HMS Goliath. The battleship had been in the area since October but she had been restricted to harbour, then sent to Simonstown for urgent work on her unreliable engines. The admiral called for reinforcements, including aircraft to bomb the German cruiser, torpedo boats for a surprise attack and shallow-draft monitors for longer-range bombardment. He also asked for extra ships to maintain the blockade of both of the Rufigi Delta area and to prevent roaming German armed forces ashore from being resupplied by sea. Goliath‘s big 12-inch guns did not have the range to hit Königsberg, so the battleship was recalled on 24 March for more promising duty in the Dardanelles. The admiral shifted his flag to Hyacinth, then Weymouth.

HMS Goliath.

Tragically, Goliath fell victim to a Turkish torpedo boat attack off Cape Helles, less than two months after leaving the delta. Around 0100 on 13 May, she was hit by three torpedoes. She capsized and took 570 of her 700 crew with her to the bottom.

Other aircraft to try their luck in the delta included three old Short Folders, brought there from Durban by the auxiliary cruiser HMS Laconia. On 25 April, just as the Anzacs were landing at Gallipoli, the newly promoted F/CMDR Cull made a reconnaissance sortie with an observer and camera in a Short. He experienced an engine failure due to enemy ground fire, but landed safely and brought back solid evidence that Königsberg was still full of fight. What the camera did not show was that nearly a third of the original 330-strong Königsberg crew had disembarked to fight ashore, by order of the German Admiralty. Colonel (then) Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck employed these men to bolster his rag-tag guerrilla army that was brilliantly harassing British forces in East Africa.

Mafia Island

Earlier in 1915, on 20 January, a small British force had taken Mafia Island, about eight miles to seaward from the delta. They constructed an airfield, eventually comprising a cleared field with a corrugated iron hangar and small living-quarters huts. The old Shorts operated from there for a few weeks but soon all three became totally unserviceable, including one that crashed after its rudder was shot away by ground fire.

A Caudron GIII at Mafia Island in 1915 (left) and a 160 hp Short Folder.

No torpedo boats were ever despatched, but the next significant event was the 3 June arrival of the monitors HMS Severn and Mersey. These low freeboard, shallow draft and unwieldy craft had been painstakingly towed by four tugs all the way from Malta, but their draft of only 4 feet 9 inches (1.45 metres) made an up-river sortie possible. Their arrival also coincided with the delivery of more ground crew plus four land planes by HMS Laurentic: two Caudron GIII biplanes with 80 hp Monosaupe Gnome engines and two Henri Farman HF27 Pushers with 140 hp Canton-Unne engines. The Henri Farmans were from a special batch built for tropical conditions, with steel tubing frames, a four-hour endurance and a temperate climate bombload of 550 lb (249.5 kg).

Naval Gunfire Support Training

Sqn/CMDR R. Cordon assumed command at Mafia Island and naval gunfire support (NGS) training commenced in earnest. Importantly, the new aircraft had wireless, but a “Plan B” flag signal system was also rehearsed. One Caudron and one Henri Farman were lost during this arduous set up, training and testing phase. The monitors were also reinforced with steel plate, sandbags and hammocks along their superstructure and main deck.

In a scheme worthy of WW II Japanese admirals, a mock diversionary attack was mounted on Dar-es-Salaam on 5 July by Laurentic. The monitors, preceded by minesweeping whalers, entered the delta via the northern Kikunja Mouth branch about 0520 on 6 July. At about the same time the remaining Caudron provided yet another diversion by bombing Königsberg from about 6000 feet but, not surprisingly, scored no hits. Simultaneously, Weymouth and Pyramus shelled targets ashore in the Kikunja Mouth while Hyacinth and Pioneer lobbed shells into the Simba-Uranga area. The tiny monitor squadron reported light artillery and heavy small arms fire from the banks but they responded with machine guns and other weapons as they pressed on.

Well dug in

The troops and artillery ashore were well dug in and camouflaged. Pioneer‘s Surgeon Lieutenant G.A. Melville-Anderson confirms this: “Previous to anchoring, a shell burst in the water not far from the ship, and another in the air. No one knew from whence they came. Very soon we were firing salvoes and then each gun rapidly independently. Our shells were bursting everywhere, throwing up great clouds of sand and earth. No sign of life was visible in the neighbourhood,” (cited in a Semaphore monograph, July 2005).

The Rufigi Delta, 6 July 1915.

Anchoring about 0630, at a supposed 11,000 yards range, the monitors expected their six-inch guns to out-range Königsberg‘s 4.1-inch cannon. Unfortunately, they were not only closer than expected, but within clear view of at least one of Königsberg‘s many spotters who were linked to the ship by a network of telephone wires. Severn opened the account at 0648 but was almost immediately straddled by the first of many accurately-laid salvos. Wisely, she shifted berth and opened the range 1000 yards, but Königsberg scored first, a direct hit at 0740 on Mersey‘s forward six-inch mount that killed four men, damaged the gun and wounded four more (Semaphore, July 2005).

First hit, 0751

F/CMDR Cull, in the remaining Henri Farman, at last signalled a hit on Königsberg at 0751, but he had to leave because he was running low on fuel. This aircraft and the Caudron continued to spot fall of shot intermittently for the rest of the day. Between them, the two monitors fired 635 rounds for three confirmed hits (Alliston p. 64) before they withdrew around 1545.

A reconnaissance flight the next day confirmed that apart from losing one forward 4.1 inch gun, Königsberg‘s seakeeping and fighting qualities remained relatively unscathed.

Fire control shift

Importantly, the monitors learned the hard way that instead of firing at their own rate under their own control, they must fire in a manner that allowed spotters to identify and correct the fall of shot and allow for shots that might not explode or be lost in nearby dense jungle.

Six days later, just before noon on 12 July, the monitors once more steamed into the delta, receiving defensive small arms fire as strong as ever, with Pioneer and the other ships again in support. Severn closed to 10,000 yards despite being straddled by a series of four-gun salvos during her approach. When Severn opened fire at 1230, Königsberg‘s accuracy suddenly slackened, due to a lucky hit severing their spotter communications network. Severn‘s eighth salvo registered a hit, according to the spotting aircraft, with eight more targets recorded from the next 12 shots. Königsberg was quickly reduced to three-gun salvos, but there was more drama in the air.

Two cylinders were shot away from the spotting Henri Farman’s engine at 1250. Königsberg‘s captain claims it was a deliberate shot from his ship with his last round of shrapnel (Alliston p. 74). However, the ship had no proximity fuses and a direct hit or near miss from a main or secondary armament shell should have caused much more damage to the frail aircraft than just a couple of shot-away cylinders.

Friendly shrapnel?

The ragged cloud base, at best, was 3000 feet, so it is probable that the aircraft was flying at 2000 feet or even lower. This puts it well within range of machinegun fire from both the ship and surrounding bush, as well as “friendly” shrapnel. There was a lot of metal in the air that day, any of which could have caused the engine damage and the concomitant “explosion” reported by the pilot. F/CMDR Cull ditched 150 yards from Mersey and one of her boats rescued the aircrew.

An ever-decreasing rate of fire and a number of large explosions shortly after 1300 signalled Königsberg‘s end. Her surviving crew abandoned ship and they set scuttling charges to fire around 1330. The monitors withdrew about 1420 to the cheers of the flagship.

The Germans reported 32 killed and 125 wounded in the battle, while the British lost six killed and four wounded. Many more were incapacitated by disease. The German delta troops, artillery and other weapons remained reportedly unscathed despite many bombardments by the cruisers and other ships. Over the ten-month blockade, the RN deployed 21 warships, four colliers and 10 aircraft. Altogether, the monitors fired 837 six-inch shells (Alliston p. 82).

In a final twist of fate, the remaining Caudron overturned on landing after its last spotting sortie on 12 July and was out of action for a “long period”. It would have been impossible for the monitors to finish off the job without an aerial spotter. It was not until August that a reconnaissance flight by F/CMDR Cull confirmed the cruiser’s destruction and coincidentally recorded that her guns were being salvaged.

Pegasus link

The Rufigi Delta saga did not quite end there because the Germans salvaged all 10 of Königsberg‘s 4.1 inch guns. They were were refurbished in Dar-es-Salaam and mounted on wheeled platforms. Two were used with great effect to resist a British attack on Kahe, in the Kilimanjaro-Aruscha area, around 21 March 1916. A little later, in June 1916, others were employed to bombard Kondoa Irangi. Ironically, in the latter action, two guns that responded to this assault were salvaged by the British from the same HMS Pegasus that Königsberg sank in Zanzibar in September 1914 (Jackson, 1985).

By the end of July, except for brief harbour visits that totalled nine days, Pioneer had been under way every day for six months, with her crew living and working in appalling conditions. The ship herself was wearing out. “On at least one occasion she went to sea with one main engine out of action,” said Jose (Jose, p 236). Her crew were looking forward to a well-earned rest and relaxation period and, perhaps, a quick cruise home to Australia. However, it was not until February 1916 that the ship was released, in conformity with earlier Admiralty promises, only to have that order smartly countermanded upon the appointment of General Smuts as the new land force commander. The cruiser spent another half a year on boring and enervating East African patrols, punctuated every now and then by brief shore bombardments of inert-looking targets and all too short dockyard visits.

NGS history

Although it probably was not appreciated at the time, Pioneer was there at the gestation of aircraft-directed naval gunfire support. This led directly to the efficient WW II and later procedures where 16-inch battleships destroyed anything from pinpoint targets to whole villages at ranges of 20 miles, all in less than thirty minutes from the time the spotter first established radio contact.

The nine 16-inch guns of the WW II-era Iowa-class battleships were devastating NGS weapons.

Independently, according to an RAF 269 Squadron report, a similar NGS operation was conducted on 24 July 1915 in the Agean with “a Short seaplane 184 spotting for HMS Roberts on target No 1 (fort)” (www.oca.269 Squadron.)

HMS Roberts was certainly at Gallipoli later on, but compared with the glacial movement of similar ships involved in the Rufigi Delta campaign, it is not clear how the monitor Roberts could possibly have been engaged in a complex NGS action at Gallipoli a mere 35 days after commissioning in the UK on 19 June 1915.

The tired old warrior Pioneer finally dropped anchor in Sydney Harbour on 22 October 1916, more than a year and nine months after leaving Fremantle. Patched up and worn out and patched up again, she paid off while her crew transferred to other ships and shore establishments. The RAN sold the gallant ship in 1924. Her hull was scuttled outside Sydney Heads in 1931.

References:

Alliston, J. The African wars 1914-16. The Naval Historical Society: Garden Island. 1996.

Bastock, J. Australian ships of war. Angus and Robertson: Sydney. 1975.

Bruce, J.M. British aeroplanes 1914-1918. Putnam: London. 1957.

Jackson, F.E. Diary of the German East Africa campaign 1914-1918, entry 23 May 1916. Military History Journal, Vol 6 No 6. 1985. SA ISSN 0026-4016.

Jose, A.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18: Vol IX Royal Australian Navy. 2nd edition. Angus and Robertson: Sydney 1935.

Semaphore. Issue 12, July 2005. Blockading German East Africa, 1915-16.

Website:

www.oca.269squadron.btinternet. co.uk/history/squadron_his-tory/269_Chronicle_Pt_1_ Narrative, p6.

I am currently preparing a book on letters published in the Camden News, Camden, NSW from WWI Soldiers & Sailors for the Camden Historical Society. As one of the letters is from an able seaman aboard HMAS Pioneer I was wondering if I could use the map on page 9 of your article “Rufigi Delta and HMAS Pioneer 1915-16”. If so could you please advise how I should reference it.

Hoping to receive your support.

The book to be published with the support of a Federal Government grant will be called “Camden’s World War I Diggers 1914-1918”. Raymond Victor Cranfield appears to have been the only Naval representative from Camden so I believe it is important to highlight his service.

.Kind regards

Janice Johnson

Thanks for your enquiry, Janice. We’re happy for you to use the map, though I don’t know it’s source. You could reference it as ‘ from the Naval Officers Club Newsletter. Original source unknown.’

Many thanks for your assistance. It is a pity that the Naval records for WWI do not appear to have survived. I hope I haven’t missed any naval personal from our nominal roll. I only found Cranfield because of the letter he wrote on the Koinigsberg.

regards

Janice