HMAS Sydney: the Vung Tau ferry

book review by Fred Lane

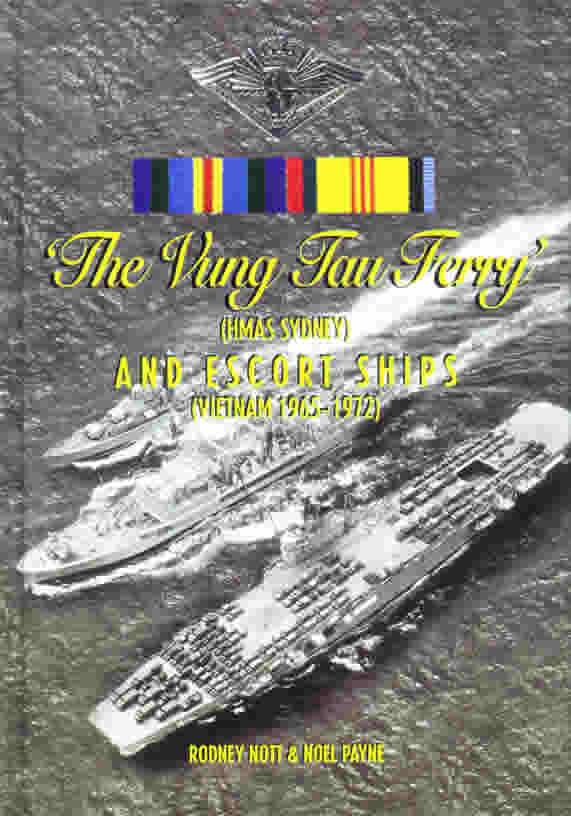

Nott R.T. and N. A. Payne (2001) The Vung Tau ferry: HMAS Sydney and escort ships. 3rd Ed. Noel and Margaret Payne: Nerang. (168 pages plus 90-odd pages of addenda such as crew lists and escort ship details. Cost $29.95. Self published hardback.)

This 258-page book is a very readable anecdotal history of the involvement of HMAS Sydney in the Vietnam War, ranging from her first voyage to Vung Tau in 1965 to her last in 1972. The main thrust and about a third of the book, by volume, never strays far from the political and legal struggle surrounding the award of the “Return from Active Service Badge” and other benefits for her crew. About another third lists details of Sydney and her ships company, also data about other RAN ships, including Jeparit and Boonaroo, who shared the logistics, escort and gun line burdens in Vietnam. Excellent photographs and charts illustrate the story.

Unfortunately, the Australian politicians of the day seem in retrospect to have been more interested in feathering their own nests, through generous pay rises and pension entitlements, than recognising the hardships and danger that went with the job of obeying their directions to maintain Australian forces in the field.

Some politicians even argued that granting honours to Sydney’s sailors might risk some paltry millions of dollars to fund possible future Defence Force Housing grants. Other senior uniformed personnel seriously argued that any campaign medal would be devalued if it was awarded to logistics people, such as Sydney’s crew.

The Australian government finally issued the Return from Active Service Badge in 1986 in response to sustained efforts by groups such as the Vietnam Logistics Support Group that formed in 1985. In 1992 they authorised the award of the Vietnam Logistics and Support Medal.

Missed opportunities

The authors criticise unnamed “academic historians” for much of the government’s position. Unfortunately, they fail to present a detailed case and reasoned argument showing how they arrived at this conclusion or even rebutting the miscreants point by point. This is a pity. They probably had the ammunition.

The book seems to be not so much a substantially original work by Nott and Payne, but more an edited compilation of articles and data by a variety of authors, including Buster Crabb and Red Merson, with interspersed editorial comment by the nominal authors. Some accounts are very real, very personal and very exciting. Others lead to assertions which, without better supporting evidence, could be easily misinterpreted as reflections of paranoia at a number of command levels. Additionally, verbatim Reports of Proceedings and Temporary Memoranda are rarely riveting or necessarily convincing. Even Churchill, never the most erudite of authors, at least placed essential excerpts of these in appendices.

There is no doubt that the good ship Sydney performed to her usual “above and beyond” standards. Her crew, many of them young teenagers and barely out of recruit school, rose to the occasion under the able leadership of their NCOs and officers. It must have been sobering for them to see a massive real life firepower demonstration on their approach to anchoring at Vung Tau.

They were also reminded of their responsibilities by precautions such as the blackout as they approached the coast. In harbour, they had armed lookout sentries, boat patrols trolling anti-swimmer harpoons, divers inspecting the ship’s bottom and random scare charges detonating. Maybe Sydney was not attacked because the Viet Cong were just not interested in her as a target. Others might argue equally forcefully that the danger was there but the ship’s aggressive defence posture deterred the enemy from even thinking about attacking.

Not mentioned was the last Sydney Vietnam logistics trip, when she loaded retiring Australian troops and equipment from Singapore, rather than Vung Tau, in 1973.

Bibliography problems

The book has a short bibliography but, oddly, no citations to these references in the main body. Furthermore, in contrast to Steve Eather’s book, Get the bloody job done, which is mentioned in the text, but not listed in the bibliography, there is no index or systematic analysis of both sides.

In short, this is a series of great anecdotal yarns about a great ship and her even greater crew. The tale is worthy of greater effort and scholarship. With just a little more work it could have been made into something much more memorable. It is perhaps a reflection of the political and publisher apathy that surrounds the subject that such a book is yet to be written and published.

References:

Eather, S. Get the bloody job done. Allen & Unwin: St Leonards, 1998.