(This article was first published in NOCN 85, 1 June 2011.)

Newsletter 84 published on 1 March 2011 contained a review of Patrick Lindsay’s new-release The Coast Watchers: Behind enemy lines, a book covering the story of the mainly-Australian irregular force which stayed behind in parts of Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands occupied by Japanese forces from 1942. These Coast Watchers provided valuable intelligence reports of enemy activity, rescued downed aviators and shipwrecked mariners, helped arrange the evacuation of non-combatants, and many of them later became guerrillas. The book review, though favourable, mentioned that in the reviewer’s opinion Lindsay had omitted several stories about the achievements of this remarkable force that were possibly worth including. This is one of those stories.

Solomon Islands

The Solomons are a chain of mountainous islands, running south east from their most northerly member, Bougainville. For much of the chain’s 580-nautical mile (nm) length, it is in fact a double chain, with a stretch of deep navigable water between them 35 to 50 nm wide. This is The Slot, which in 1942 became the favoured route for the Japanese logistic supply line to Guadalcanal, the string of destroyers known as The Tokyo Express, in sustaining the increasingly-beleaguered Japanese land forces there.

By July 1943 Japanese forces had been ousted from Guadalcanal, but they were still well established in several places in the central Solomons, mainly in the collection of smaller islands on the southern side of The Slot known as the New Georgia Group. The Tokyo Express continued to operate to sustain these forces, and the waters of The Slot were continually disputed by the naval forces of both sides. No place on earth has seen such a sustained series of naval engagements as The Slot saw in 1942-43, and naval historians recognise 12 or 13 major battles. The allies lost four cruisers in the very first engagement, but soon the Japanese suffered heavy losses too, including two battleships.

Coast Watchers on station

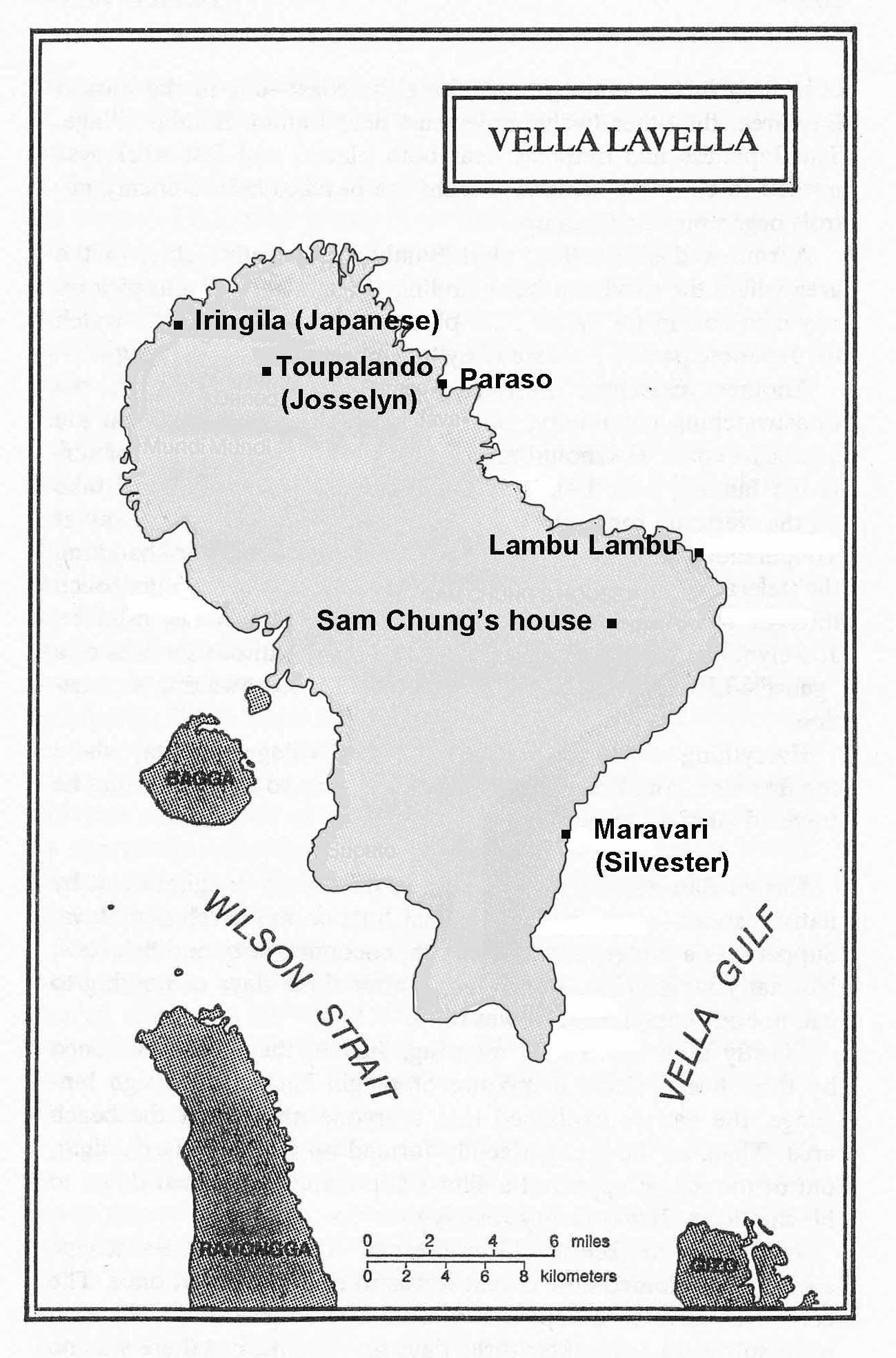

A handful of allied Coast Watchers were established around and near the New Georgia Group: there was one station on Choiseul, on the northern side of The Slot; on the southern side, one at Segi, in the south-east of New Georgia Group, and one on Vella Lavella, at the north-western end of New Georgia Group.

The Coast Watcher on Vella Lavella was LEUT Henry Josselyn RANVR, an Englishman who was formerly a District Officer in the administration of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. Eric Feldt’s first description of him was “small, cheerful and assured”; later, he described him, with good reason, as “a pirate”. By the time this story starts, Josselyn had already experienced full-on action with the USMC: he was a guide for the Marines in the first wave of landings on Tulagi some months previously, during which action his conduct earned him the Silver Star.

As his deputy, Josselyn had an Australian, SBLT Robert Firth RANVR, a former Burns Philp accountant and ship’s purser. The remainder of the station staff are not recorded in published histories, but were almost certainly all Solomon Islanders to act as carriers, messengers and scouts, numbering probably between 15 and 30. Josselyn had established the station in mid-October 1942; Firth came along several months later.

Incredibly, there was a strong force of Japanese – 300 to 400 troops – spread over various locations on Vella Lavella, with their main base at Iringila about two miles from one of the Coast Watchers’ camps. (Josselyn moved regularly, between about four suitable locations.) It seems almost inevitable that the Japanese knew about their neighbours, and Josselyn certainly knew about his. There was no contact, but Josselyn used to cheekily scout right up to the Japanese perimeter. Once he asked his controlling station for permission to go inside to steal a pair of binoculars, explaining that he lost his in his first landing on the island; permission was promptly refused.

The poacher

But other targets were available for Josselyn, the would-be poacher. With the number of Japanese ships being sunk by air attack as a result of the Coast Watchers’ reports, there was plenty of flotsam about. Drums of petrol and rice would obligingly float ashore; they were picked up and hidden in the jungle by the scouts. Twice, Japanese ships disabled by air attacks and abandoned by their crews, drifted near the island allowing Josselyn to indulge his flair for piracy. All available papers and documents were first collected for intelligence purposes, then it was batteries, radio equipment and parts, food, cutlery, linen, and small arms and ammunition. His camp became really comfortable, with food stocks that would last a long time. That was a stroke of luck!

Yet another action in The Slot

On 5 July 1943 USN TG 36.1 under RADM W L Ainsworth USN — comprising light cruisers USSs Helena, Honolulu and St Louis plus four destroyers — was directed to intercept another mission of the Tokyo Express — 10 destroyers — on its way down The Slot. Contact was made near the volcano of Kolombangara at 0106 on 6 July 1943, and the cruisers engaged at 0157. Unfortunately for Helena, she had expended all her flashless powder the previous night and had to use smokeless. This made her an excellent aiming point for the enemy. Her personal reward was three Long Lance torpedoes; the ship sank in 20 minutes. Helena was not the USN’s only loss that night: PT-109 (LTJG J F Kennedy USNR) which was engaged on a different mission against the same target, was rammed and sunk by an escaping Japanese destroyer in the aftermath. The Japanese lost two destroyers.

Helena’s sinking was within about 20 nm of Vella Lavella. Nearly 750 of her crew were rescued during the night by two US destroyers from the TG, but the rescue was interrupted by the arrival of Japanese destroyers which had to be engaged. With dawn the two US destroyers withdrew under threat of Japanese air attacks from the nearby strip at Munda. Many survivors remained in the water or on makeshift flotation devices. Fortunately the waters around the Solomons are warm, and loss of body heat was not a problem.

Survival

The survivors could see that land was a long way off; too far to contemplate reaching it by swimming. They spent all of the day and the next night in the water, except for the lucky few, mostly injured, who had been awarded places in what few rafts there were (including two that survived a drop by a Hudson bomber on 6 July). During their second night in the water, several of the survivors just slipped away or died.

Dry land at last

Dawn on 7 July saw land much closer, and even reachable. Though most of them were oblivious to the fact, it was the eastern coast of Vella Lavella. In the afternoon, they started straggling ashore. Some were helped by Islanders in native canoes, and some made it on their own. They came ashore along the north-eastern part of the island, in two main groups.

At the time, Josselyn’s camp was at Toupalando, near the north end of the island, and close to the main Japanese camp at Iringila. Word about the survivors quickly reached the Coast Watchers’ camp by runners, and contact was made with the island chieftain, named Bamboo, with whom Josselyn had excellent rapport. Canoes were sent to look for more men in the water; sentries were posted to watch for Japanese patrols; the locals stood by to help with food and housing for the exhausted men. They were coming ashore at two main locations: at Paraso in the north east, and near Lambu Lambu on the eastern extremity of the island. The Japanese had outposts near both places.

Word was also passed by radio to the Methodist mission station at Maravari, in the south east, where Reverend A W E Silvester remained at his post despite World War II raging all around him. Josselyn walked all night to get to Paraso, and Silvester moved to make contact with the group who had landed near Lambu Lambu. It was imperative to get the survivors off the beach and further into the interior where they would be more secure.

A village is born

The southern group numbered 104. In dribs and drabs the locals moved them inland to a wooden shack that was the home of a Chinese trader named Sam Chung. It became a hospital for the wounded and injured. Nearby, the Islanders quickly built a roofed dwelling out of native materials that was big enough to provide shelter for the rest. The senior officer of the group, Helena’s CIC officer, was LCDR Jack Chew. He realised that he no longer had a group of castaways; he had a village. He set people to work on domestic tasks, and a daily routine developed. Food was short, but there was enough to get by. Reverend Silvester provided invaluable help with medicines and dressings and dropped by every evening; he quickly developed a close bond with Chew, and soon, with all of them. Security was the domain of Major Kelly USMC, and he selected a security detail known as Kelly’s Irregulars. Two pistols came ashore with the survivors, and Josselyn sent them a mixed bag of rifles and some ammunition; Kelly gratefully accepted them all for his small force. The Irregulars saw action too: a four-man Japanese patrol came too close; three were wiped out in an ambush, and the survivor was reluctantly executed. Later, a 20-man patrol was detected coming up the track from Lambu Lambu. Fortunately it turned back before contact.

The northen group of survivors

There were 61 survivors in the northern group inland from Paraso. It is not known to what extent Josselyn was keeping contact with them, but it is known that he was also busy trying to co-ordinate arrangements for the pick-up of all the survivors. COMSOPAC would provide two destroyer-transports, but the mechanics of managing it at the island end were a headache. It was not possible to contemplate assembling everybody in one place for the evacuation, and the original plan was to move the groups out independently on two nights: 12 July for the northern group and 15 July for the southern. However the first date kept moving right as a result of the available USN forces having to deal with the unpredictable movements of the Tokyo Express — which was now delivering to Kolombangara, the volcano just 15 nm to the east on the other side of the gulf. Eventually it was agreed that the evacuation would be two pick-ups on one night, with the first being the northern group from Paraso at 0200 on 16 July, and the southern group subsequently.

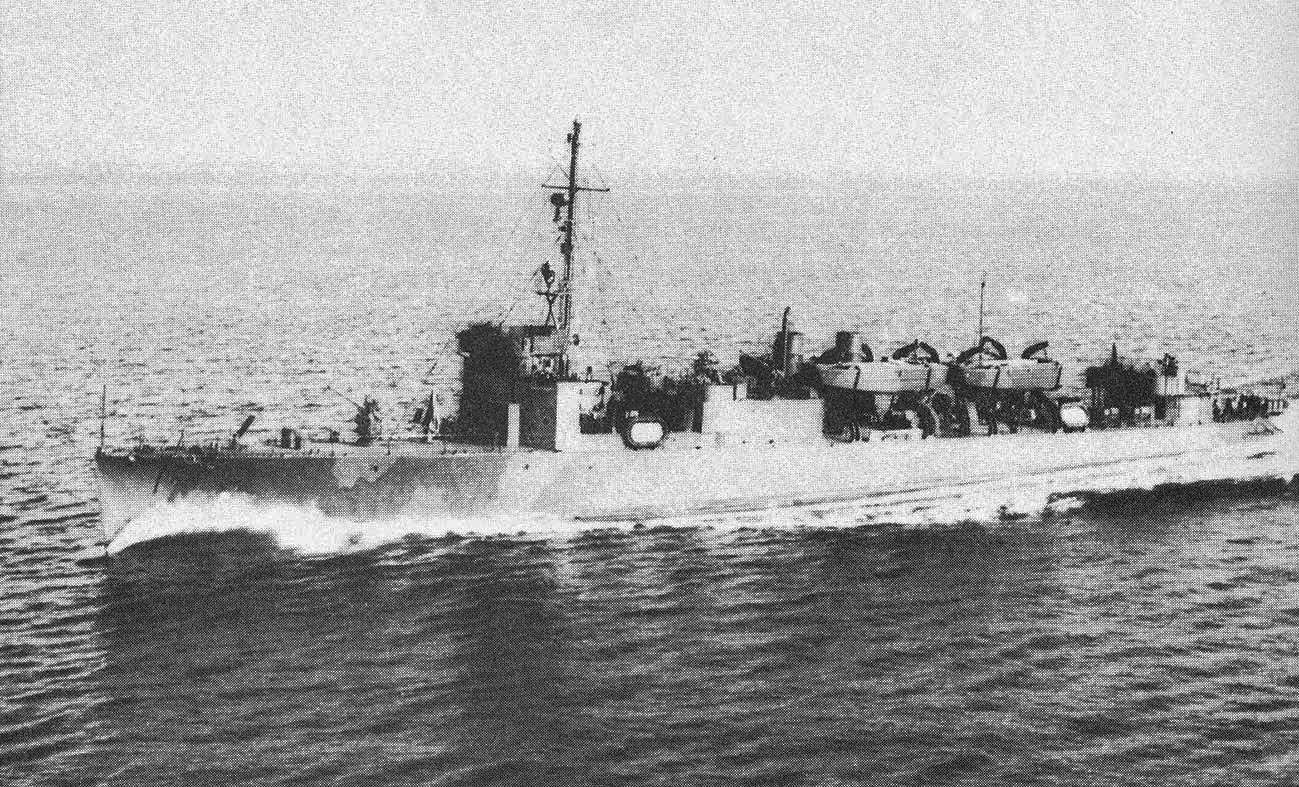

Josselyn wasn’t told in advance, but the responsible operational authority, VADM Kelly Turner USN, was determined to ensure that there would be no enemy interference in the operation. The destroyer-transports (known as APDs) were very lightly armed. Turner allocated a close escort of four destroyers, and a support force of four more destroyers to deal with vessels coming down The Slot: the evacuation force was 10 ships in total. Turner wanted to ensure that people understood that the US Navy looked after its own.

Despite minor hiccups of late arrival (causing great anxiety to Josselyn and the evacuees) and imperfect recognition signals, the evacuation proceeded almost like clockwork.

The pick-up at Paraso

The APD’s, USSs Dent and Waters, came as close in to shore at Paraso as could reasonably be expected. Josselyn was there in a canoe, and was the first man on board. The OTC of the two APDs was Commander John Sweeney USN; he knew Josselyn, having landed him with the marines at Tulagi a year ago. But he didn’t know there would be two pick-ups; this basic piece of information had been omitted from his orders. Don’t worry, said Josselyn; I’ll guide you there. It had been a tense few days for him. He had been moving the teleradio after every transmission, and shifting camp every night. He knew that the Japanese were getting close to the southern group.

The Paraso pick-up was from a sheltered river mouth, and proceeded very quickly using Higgins boats — a type of landing craft. There were two extra people, both downed pilots; one of them had flown a P-38 Lightning; the other had flown a Zero. It had been decided that the Zero pilot should be executed, but nobody could be found to do the job. As a compromise he was blindfolded and stripped to his underpants. (One of the gunners from Helena’s crew wore his flying suit.)

Tense situation at Lambu Lambu

At Lambu Lambu it was also a river pick-up, but further up river; some fine navigation up and down a bendy channel in darkness was needed. Silvester had planned it well: he had Islanders standing up to chest-deep in the water to mark edges of the shallow patches. There were extra travellers here too: Sam Chung, the Chinese trader, with family and camp followers numbering about 10 in all (one report says 16).

Tension prevailed at the embarkation point: the area was subject to random patrolling by Japanese garrison troops. Kelly’s Irregulars maintained patrolling watch between the evacuees and the likely direction of threat; none developed. Gradually, as the crowd thinned, the Irregulars withdrew towards the embarkation point. As they boarded the boats, each passed his rifle and ammunition to one of the island scouts. Kelly watched the last rifle handed over, then boarded himself. LCDR Jack Chew, as senior officer, was last to leave. He conveyed his thanks to Josselyn, who he had just met, then turned to his new and close friend Silvester. He didn’t have words to convey what he felt, so this superstitious old sailor gave the Reverend the most precious thing he had, that had accompanied him everywhere most of his life: his lucky silver dollar. Silvester and Josselyn gave a last wave and faded into the jungle.

Josselyn’s position

The bulk of this story has come from Walter Lord, who interviewed about twenty of Helena’s crew who reached Vella Lavella, Sweeney (who commanded Dent in the pick-up), Josselyn and his deputy, Firth. But strangely, Lord’s account says little about what the two Coast Watchers were doing during the time the survivors spent on the island. One can therefore only speculate on the ethical and tactical difficulties which Josselyn had been facing throughout this saga. He was charged with responsibility for the safety and evacuation of over 160 people from a relatively small island occupied by a considerable number of well-armed enemy troops. It is hard to conceive that the Japanese did not know that some survivors of Helena had made it to shore, even if they did not know how many or where they were.

The very presence of such a large number of USN sailors on Vella Lavella was a threat to the security of the Coast Watchers’ station, and therefore to its primary role of intelligence collection. But the vast number of survivors must have carried such weight that their rescue became, for the time being, the station’s primary role, with intelligence collection placed on the back burner. Josselyn and Firth probably avoided contact with the survivors as far as possible, while ensuring that their charges were kept well hidden and adequately provided for. How were they fed? The islanders lived on a subsistence economy, and this number of people would have strained supplies to the limit. Perhaps Josselyn was able to dig into the cached gleanings from his poaching expeditions.

However it was that Josselyn managed things, he got it right. He employed the meagre resources at his disposal to achieve the desired result: the 165 survivors stayed secure on Vella Lavella for almost nine days, and were evacuated with none lost.

A dominant factor in the success of the operation was that Josselyn had the total loyalty and co-operation of the Islanders, without which the rescue could never have succeeded. Such devotion doesn’t come automatically: it has to be earned. Josselyn clearly had the right stuff.

Nor was this the only rescue achieved by Josselyn: Lord’s book lists a total of 118 allied airmen rescued by Coast Watchers in the Solomons campaign. Vella Lavella was involved in the rescue of 31 of them – more than any other island.

Postscript

Lord (from his interview with Sweeney – by then a retired Rear Admiral) reports that as they steamed for Tulagi after the pick-up, Sweeney had wondered what motivated people like Josselyn to do what they did. He had offered him a ride to Tulagi, which Josselyn politely declined because he still had responsibilities on Vella Lavella. He offered cases of canned food to supplement his meagre ration stocks; that was declined too because the cans and packing material could reveal his position. “Can’t we do anything for you?” Sweeney asked.

Josselyn said that he could use two pairs of black socks, some Worcestershire sauce, and some confectionery. Whether he received those items is unknown – but we do know that Josselyn was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to go with his Silver Star.

References:

Feldt E. The Coast Watchers. Oxford University Press: London. 1946.

Lord W. Lonely vigil: Coastwatchers of the Solomons. The Viking Press, NY. 1976.

Picture and graphic captions:

Lieutenant Henry Josselyn RANVR

Map of Vella Lavella

USS Helena, CL-50. The cruiser took three torpedoes, and sank in 20 minutes in the early hours of 6 July 1943. The majority of her crew survived, and 750 were picked up by escorts before dawn.

The Reverend A W E Silvester

Destroyer-Transport (APD) USS Dent, which, with USS Waters, evacuated the survivors of USS Helena from Vella Lavella.Two Higgins Boats can be seen on the port side of the superstructure, just abaft of midships.

Aerial seascape with clouds; line of four destroyers just discernible only from their prominent wakes. The Tokyo Express on the job