The Coast Watchers:

Behind enemy lines; the men who saved the Pacific

Book review by Jerry Lattin

Lindsay, Patrick: The Coast Watchers: Behind enemy lines; the men who saved the Pacific. William Heinemann (London) 2010; Random House Australia. 416 pp; $34.95 (paperback).

The Coast Watchers were an organised force established in the 1920s to observe and report shipping and aircraft movements visible from the coast. Its members were recruited initially from expatriate private citizens and government officials mainly in what are now PNG and Solomon Islands – then under colonial rule by Australia and UK respectively. With the beginning of World War II, the force went on a war footing; members were given ‘protective’ military rank, and measures were put in place for them to be supported by local labour and police.

When Japan entered the war, and subsequently occupied parts of the area, the Coast Watchers became the stuff of legend. Many operated for months behind enemy lines, isolated and invisible, maintaining a flow of useful — sometimes vital — intelligence, rescuing stranded allied airmen and distressed mariners, and helping to evacuate non-combatants. Their influence on the Pacific war was considerable.

The achievements of the Coast Watchers are well recorded in official histories, and are known in outline by most people with an interest in the Pacific war. But strangely, general accounts of their achievements are recounted in only two published historical works: The Coast Watchers by Eric Feldt (1946), and Lonely Vigil: Coastwatchers of the Solomons (1977) by Walter Lord. The first of these is a general history of the organisation written by the man who largely created it, and ran it for much of the war. It is therefore unquestionably an authoritative and comprehensive history, but hardly an objective one. Walter Lord, an American popular historian, later produced a book narrower in scope than Feldt’s, confined to activities in Solomons. It is well written, entertaining and interesting. Both these works are available second hand.

Other existing works on the Coast Watchers, numbering a handful, are mostly personal memoirs, and deal with small fragments of a big picture. Most of them are now virtually unobtainable.

Patrick Lindsay’s work is therefore a most welcome and timely addition to the relatively scarce published material available on the topic. It is reasonably comprehensive, and while it breaks no new ground, it is more than a regurgitation of material already written. It sets the scene well, paints colourful pictures of characters, and devotes several opening chapters to establishing the strategic context in which events occurred.

Feldt, a graduate of the Royal Australian Naval College (RANC), had been in the first college intake in 1913. He served at sea in WW I and made Lieutenant before resigning in 1920. He joined the Australian administration in New Guinea and acquitted himself well, rising to the rank of District Officer. In April 1939, recognising that war was likely, Feldt transferred back to the RAN’s Emergency List of Officers. In August 1939, a month before war was declared, he was approached by a former RANC classmate, Lieutenant Commander R B M Long, then Director of Naval Intelligence, to revamp the existing Coast Watching organisation and put it on a war footing. Feldt jumped at the task; by September he was travelling through the islands by all available means, assessing the members of the organisation and recruiting new ones. As his deputy, he later took on board yet another classmate from the RANC: Lieutenant Hugh Mackenzie, who had been invalided out of the RAN with poor eyesight, and also worked in New Guinea as a planter. Mackenzie’s first assignment was as Naval Intelligence Officer to Lark Force, the army garrison on its way to Rabaul — and more of that later.

Essential to the organisation’s proper functioning were decent radio communications. The only practical radio option available for the task was high frequency, also known as short-wave. Feldt gave his Coast Watchers the AWA 3B teleradio. It was robust, and its communications performance was adequate. But it was bulky. It was driven by car batteries, that had to be re-charged on a petrol-driven charger. The set itself was three one-man loads; its back-up of batteries, charger, petrol supplies, antenna equipment and necessary spares boosted its carrier requirements to between 12 and 16 men. Coast Watchers didn’t travel light.

The book describes very adequately the key elements of the war in which Coast Watchers played a part.

These included the evacuation of the defeated Australian garrison at Rabaul in January 1942, in which a Coast Watcher, Keith McCarthy, and two army officers with the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit (ANGAU — Papua and New Guinea were now under military rule) organised the escape routes and brought to safety about 450 men of the original 1400-strong force. Among the successful evacuees was Hugh Mackenzie, their Naval Intelligence Officer and Feldt’s deputy. (Virtually all of the rest never survived the war, though most were lost when their POW ship, SS Montevideo Maru, was sunk by a USN submarine.)

During the first six months of the Japanese occupation, several Coast Watchers were captured in New Ireland and New Britain. Despite their ‘protective’ military rank, nearly all were executed; only two survived the war. Execution was not confined to Coast Watchers, it was a fate met by civilians too, including missionaries — some of them from neutral countries — who stayed at their posts tending their flock. But as the war grew older, Coast Watchers became smarter. They practiced much tighter communications procedures, disguised their positions better, and were prepared to move at a moment’s notice. Few more were caught.

Central to any Coast Watcher’s history were the services rendered by Jack Read in northern Bougainville, and Paul Mason in the south. The US Marines on Guadalcanal had no carrier-based air cover, with only their P38s at Henderson Field for air defence. Japanese land forces were all around them and were reinforced almost every night; the American logistic chain was fragile and infrequent. Japanese land-based bombers were within easy range. Read and Mason between them were able to give precise details of nearly every incoming raid, in time to get the P38s airborne and high, and AA stood-to. This crucial intelligence served the Marines for several critical months, but was achieved only by Read and Mason playing cat-and-mouse to remain ahead of their pursuers. They were never caught

Hugh Mackenzie also played a key role on Guadalcanal. Several Coast Watchers were actually on the island but well beyond the Henderson perimeter. They provided accurate and timely information on enemy troop, shipping and aircraft movements that helped ensure the security of the lodgement. Their activities and radio traffic were co-ordinated by Mackenzie under his famous radio callsign KEN.

Lindsay tells these and other stories well, illuminating them from several sides and adding colour to the characters. Naturally he had to be selective in what minor events and anecdotes he included, and he missed a few that this reviewer would have thought appropriate for inclusion — but that’s just a personal view.

The author also declined a chance to break new ground. The later editions of Feldt’s book describe the second phase of the Coast Watchers’ war, when some of them became guerrillas — mainly on Bougainville and New Britain. The fact that the guerrillas took over 5400 enemy lives for the loss of only 47 Coast Watchers and support staff speaks for itself. Tellingly, Feldt commented that the necessity of pursuing these operations was debatable, since the remaining Japanese were cut off and isolated. Lindsay chose not to re-open the ethical issue raised by Feldt, though he does deal with the guerrillas.

***

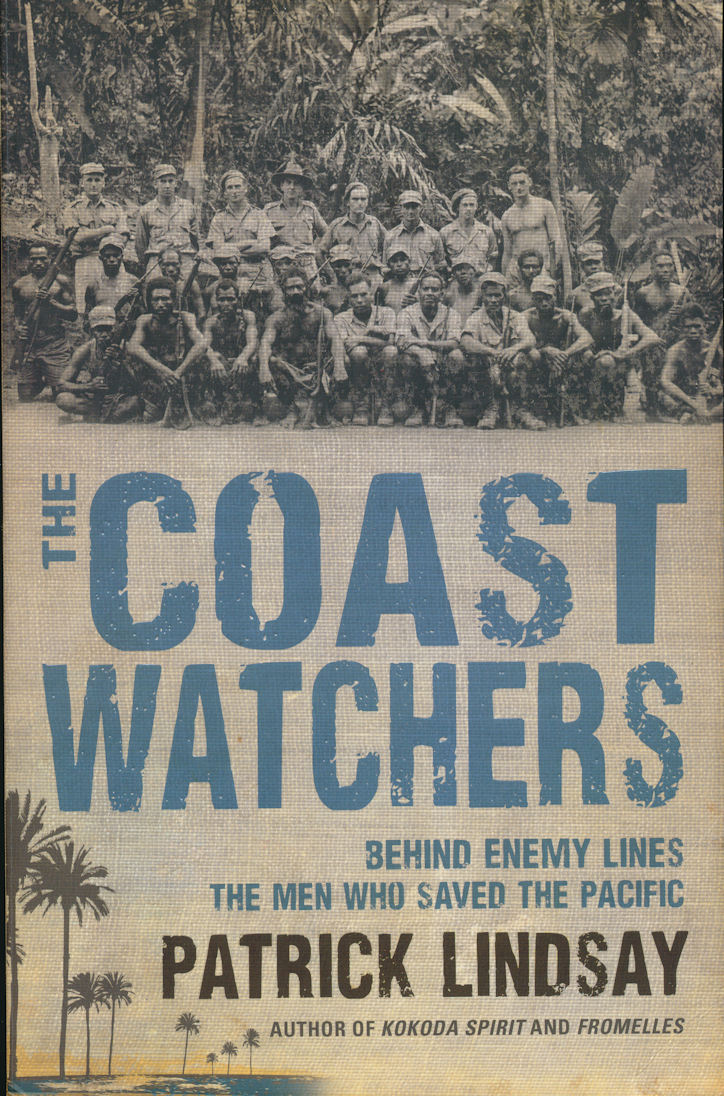

The book is well illustrated with black-and-white photographs, mostly new to this reviewer. All maps are grouped together at the front of the book. They are generally adequate, bar one: Mason’s escape-and-evasion activities on Bougainville took him from one end of the island to the other, and are described in detail in the text. But it’s impossible to recreate them from the highly-simplified map provided of the island. Locations mentioned in the text could have been included on the map; better still, show Mason’s track. Mason’s is a gripping story, and deserved better treatment.

This book is a new release that re-tells a slice of history in fresh language and will re-awaken interest in the impressive achievements of Commander Eric Feldt OBE RAN and his team. It is highly recommended to readers with an interest in RAN history and the history of the Pacific war.